You probably haven’t built a power plant…

But our guest has!

John Polomny has an abiding passion for all things energy related. And while being part of a team that builds power plants doesn’t automatically make one an expert in the business of investing in the sector… he’s done the requisite work.

John’s knowledge of the energy sector has translated into a knack for identifying out-of-favor, mispriced industries—like uranium, for example.

Listen and learn how John educated himself on energy investing, the folks he followed on his journey, and the industries he thinks offer great value [26:52].

The Mike Alkin Show | 59

Self-taught investor says don’t miss these mispriced industries

Announcer: Free and clear of the chatter from Wall Street, you’re listening to Talking Stocks over a Beer, hosted by hedge fund veteran and newsletter writer, Mike Alkin, who helps ordinary investors level the playing field against the pros by bringing you market insights and interviews with corporate executives and institutional investors. Mike sifts through all the noise of mainstream financial media and Wall Street to help you focus on what really matters in the markets. And now, here is your host, Mike Alkin.

Mike Alkin: It’s Monday, May 6th, 2019. Hope you had a nice weekend. It was a bitter end to my NHL fan watching season, at least for the home town team, as the Islanders got absolutely smoked by the Carolina Hurricanes. Excuse me, who are just playing tremendous hockey. I mean they dominated the Islanders in every facet of the game. The Islanders finally met a team that hustles and is disciplined like they are, but they have a lot more skilled players than the Islanders do. So it was a romp. I mean the first two games were close, but games three and four, it was a mess. Islanders just couldn’t get it going. They were just outplayed in every facet, like I said.

But it was interesting because Friday night was my daughter’s confirmation dinner. Before she got her confirmation at church on Sunday, and Friday night the pastor and all the leaders of the confirmation class which she’s been going through for two years now, they had a dinner where they talked about each kid in the class. And they did a nice little video, a montage and all that stuff. But it was Friday night, and Friday night was game four of the Islander game, and I didn’t realize we had the dinner, and the dinner started at seven and so did the game. So all day Friday, I talked to my wife, and I’d say, “You know, I think I’m coming down with something.”

And she said, “Really? Seriously? I never give you a hard time about watching hockey. I love that you do. But how many times is she going to get confirmed?” I said, “I absolutely understand, but I don’t know the next time the Islanders are going to be down three games to none.” And she said, “Not even. Not even then. Not even funny. Don’t even try.” But she did give me a hall pass at the dinner, so I probably went to the bathroom 30 times to go check the score, pop on a video. Although down at the church, the reception wasn’t great, the data, so I had to go outside a few times. And my daughter knew. She was great. She knew Dad was going to check the score, so she was okay with that.

And I am, I mean my family, we’re Christian, we go to church occasionally, although I’m not great. I was raised a Catholic, and I was an altar boy and I did all that stuff. And I was raised by my grandparents and my grandfather was a very, very religious Catholic, an Italian immigrant, and he used to go to church every day on his way to work, and light a candle, and he was a very religious man. And so I did my thing. I did the altar boy stuff, and then I kind of rebelled a little bit, I think, from having it be force fed to me over the years. But we do our thing. We’re not regular church goers, but we go, and my wife’s a huge volunteer with everything with the schools and with the church.

She’s always, always out helping and doing something, and so is my daughter. And the way I like to do it, is as the church sometimes, we don’t have him anymore, but we had an associate pastor and it seemed like sometimes that some of these services would go for an hour and a half, an hour and 45 minutes, and I’d just, my son would be fading. I’d be like, oh God, no pun intended. But I found when, one of our associate pastor’s who’s no longer there, he was great. When I had partial ownership of a hard cider company, he liked hard cider, and I would text him right before service started. And I’d say, “Listen, if you could keep this under an hour, just keep it under an hour, a case of hard cider.” He was a good guy, big sports fan, and I can’t tell you how many times he delivered. So it was good.

It just took a little bit of hard cider to get that done. Anyway, it was a very nice Friday evening dinner. Sunday was very nice. My daughter had a nice, we had family over and friends over, so it was nice. But like I said, the Islanders got outplayed. They had a great season. Nobody expected them to make the playoffs, so it’s nice when you get to rally around it and everyone’s talking about it and feel a little sense of community pride. Probably, oh gosh, a third to half of the Islanders live in my little home town here, so it was nice to see them around town and stuff like that. So anyway. But it was interesting. Before we had … we went to a brunch at our club, and before we came back to the house, and we were talking, all my family was there, and the kids are getting older now.

A bunch of the cousins are in high school, and thinking about college and stuff, and it was [inaudible 00:06:19]. We were talking about colleges, and one of my nephews is … not, a couple of my nieces … my niece is a fabulous student and she’s going off to college next year. And one of my nephews is a very, very bright boy, but he school’s not his thing. He doesn’t care to do it, and he’s going to a trade school, and he’s going to be a plumber, and he’s doing fantastic. And it got me to thinking, we were talking about it, we were talking with my niece, and she was saying, she has great grades and great test scores, and she was saying how many kids with phenomenal grades, phenomenal scores, can’t even sniff some of the top schools.

And I’m talking kids with 102 grade point averages, above 100. It’s weighted, with near perfect SAT scores, that can’t get in. They’ll apply to countless number of top schools, and they might be wait listed. And I hear that here in my town, a lot of overachieving kids, read, pressure, and then they have a hard time getting into the schools that they want to. And it just made me realize how competitive it is, and I think about … like here’s so many kids, and a lot of these kids that want to … some may want to go. Some may not. But from an early age, the pressure to overachieve or to get great grades. I will say in our house, that’s not how we structure it.

As long as you put in your best effort, my kids happen to get good grades, but it’s about what you get out of it. My wife is, she’s a CPA, but she also has a master’s in education, and so education is a passionate thing for her, and she’s always up in arms about how kids learn in the US and how it’s force fed, and you are learning just to a test grade, just to achieve a grade, and then you move on and the kids forget, rather than it being iterative. And she points to, I think it’s Sweden or Norway where it’s much more inclusionary. So anyway, but it got me thinking, and I was thinking, I have looked at over the year the for profit education space, and I looked at other sectors and educational wise, and companies that provide systems to the education industry.

And it was so many kids, I think, I don’t know where it starts, but there’s this view that you have to go to school, get great grades, go to the top schools, and everyone just goes for that golden ticket. And I struggle with that, because I think kids have to find their own way. Some kids just might not be suited for school. Some kids don’t learn that. And I think about so many successful people I’ve met in my life and the entrepreneurs that I’ve met that may not have gone to college, or they went to college and they dropped out because it wasn’t for them, and they found their way. And I think about, I was telling my nephew yesterday. I said, “You know, you’re going to come out at 20, 21 years old with a trade, and who knows where you’ll go with that?”

He happens to be entrepreneurial. “So, you’re going to be a plumber, and maybe you’ll be a union plumber, maybe you’ll work for someone in a nonunion business, but you’ll be making a lot of money. They make a ton of money, especially for young people, and who knows where you’ll go with that. It’s then have the skills to understand how to save your money, how to structure it so that you could do a little investing with it, you could save with it. Sure, you’re a young guy and you’re going to go out and blow a little bit of money too, that’s normal.” But from there, that’s a nice head start when kids are just coming out of school with lot of student loans. He’s going to … or parents having the loans … he’s going to come out with a nice income, and who knows? The world is his oyster.

And I think that seeing what I see now, my daughter’s in ninth grade, so she’s not quite there yet, but we live in a community where all these kids are older and we have friends, and you just see the pressure that comes towards these kids. And I don’t know that that is the recipe for success. Do we create just a lot of little robots that are just testing, just getting grades to get into a school? It made me think about that college admission scandal, the lunacy behind these parents, what they were doing to get their kids, just made the hair on the back of my neck stand up, I wanted to throw up. And it got me to thinking about my career in the hedge fund industry for 20 plus years now.

And I think about it, and I think I mentioned early, or if you listened to the podcast, I went to a university where it didn’t, after a couple of years, I wasn’t a good student. So I wound up coming home, and I worked, and then I wound up going to a local commuter college, where I finally, in my mid-ish 20s, decided that I needed to really buckle down. And it wasn’t that I didn’t … I didn’t consciously think that the first time around, but I was playing hockey, I wasn’t focused, I didn’t have the structure growing up, education-wise, from my grandparents who didn’t finish middle school. So for me, it was a learning experience, and went to a little nondescript school that nobody was recruiting at.

And I wound up literally in New York City at Wall Street working at some monster hedge funds, at really big ones. And through hard work and perseverance and a stroke of luck, and next think you know I’m there, and I’m sitting there amongst all these really, really bright people, and with huge pedigree, great Ivy League schools, the top schools outside the Ivy League, MBAs, so on and so forth. And you talk about being intimidated at first, but after a few years and you’re in it, just like anything else, you realize, wow, there’s some really smart people who went to those schools, and they’re all smart. But some of them might not have good instincts. Some of them might not be equipped to do this.

And like anything, it sorts itself out, and the cream rise and those who aren’t cut out for it drift and do other things. But for me, it really cemented in my mind that it’s the effort you put into it. If you have baseline intelligence and you are able to then really work hard and put in the effort and constantly learn and be creative and be open minded, that the world is your oyster, and that you can achieve really good things, even if you didn’t have that pedigree. And as I started talking to CEOs and CFOs around the world, you realize, not everyone went to an Ivy League school, and some people went and took the same track that I did, and they had really successful careers.

So it made me think about all the pressure kids are under from parents, whether it’s sports or whether it’s education. Now don’t get me wrong. Like I said, we put structure around the kids and we make them do their work, and my son, my daughter, you don’t have to make do the work. My son, he can fade when he wants to with education, so we got to stay on top of him a little bit, but as we’re growing, I’m constantly learning as a parent, and many of you are listening and you’ve been through this before, so you’re probably laughing saying yeah, you just wait. But it really, and seeing how it is, and the college admission scandal thing really just triggered me, I think, with how it is.

So as I think about it, and I think, I apply so much to investing, and I see all of this as … this is where I’m going with this … I see all of these quote gurus, these experts, these geniuses who were brought on, you watch them on CNBC, you watch them on Bloomberg, or they’re interviewed somewhere. You don’t know who they are. You have no idea. He might work at a great shop, he might be pedigreed, but it doesn’t mean anything. Doesn’t mean that he’s a great investor. It means maybe they work for a great firm that has a good PR thing. And eventually, some people … now some people have been there a long time and you’ll know their track record, but a lot of them you’re not going to know.

And that got me thinking with all this … I’m fairly active on Twitter. I don’t post a lot, but I read a lot, and once in a while I’ll post something. But having a podcast, people come at me from all directions, and I’m being on Twitter and people think of me as the uranium guy, which I’m not, but I run a uranium fund, and I think I know a fair amount about it. But I’m not a uranium quote expert, but I’m a supply, demand guy, and I know the uranium fuel cycle really well. But that’s all in the last four years. That was upon myself. I take that upon myself to learn it. And now I had a good background of 20 years plus to understand what to look for in investing, deeply cyclical industries, replace X, Y, Z industry with uranium and do that work, and then learn about the particulars of that.

But that didn’t require … that’s not high finance. That’s fourth grade math. That’s effort. That’s digging. That’s constantly researching and asking people questions and not being afraid to look dumb, and saying, “I don’t understand this. Can you explain this to me?” And almost everyone listening to this podcast can do that, can absolutely do that. It doesn’t require a degree in finance. It doesn’t require an MBA. It doesn’t require a CFA. And I do the podcast because I try and break down the basics of investing for regular folks. I’ve said it a lot before, if you’re a professional investor, you’re not going to get a lot out of listening to this because you know what I know.

Maybe about uranium I’ll probably share some insights you’re not aware of if I talk subject matter on uranium or nuclear power or nuclear fuel. That might or might not, but likely will leave you with some insights that you might not have had before based upon my learnings and applying an investor’s view to it. But one of the things I’ve noticed being on Twitter, especially in the case of Tesla. When I look at the Tesla Q, it’s called, and the Q is the symbol when a company goes bankrupt, that’s what they put next to it on the symbol. And there is this crowdsourced group of investors who think that eventually, Tesla will go bankrupt, and they call themselves Tesla Q. And it’s great.

But I know a few of them, and some of them are professional investors, but there are many that are not. Many are just from all walks of life. And I read the stuff talking, they call it FUD, fear uncertainty, and doubt. The Wongs say that the Tesla Q spreads FUD. I can’t even begin to tell you how good the work is from the folks who have an opposing view, who believe Tesla’s assured, this crowdsourced group of work from people, many outside the industry, who have expertise in different areas or don’t, but take the time to learn. And when it’s blended with the work of those, you see the folks who are financial guys, and I can tell who is and who isn’t by reading it, the nuance, the language they use, and so on and so forth.

But there are people out there who don’t have finance backgrounds who have absolutely nailed what’s going on at this company. And you can apply that to anything. So I love reading, and I’m a voracious reader, but especially when talking about investing, and how do you get your information? How do you generate your ideas? I look at a lot of … especially on Twitter, just random stuff, or on YouTube, and you could see people who may not be professional investors, but who have endeavored to learn and find who the great investors were and learn about their styles, and understand how to think. And that’s the beautiful thing about the markets. If there are people investing, if you’re investing for your own money, it’s a constant evolution.

Now, I happen to be an investor who takes the other side of consensus. Now I don’t do that just to do it, because you’ll get your head handed to you if you do that, but I am of the opinion that you … so they call it contrarian, right, call it whatever you want. It’s just nonconsensual thinking. And in doing so, you’re going against the crowd, excuse me, all the time, in a situation where you think the crowd is wrong. So if you’ve done your work and you’ve done a deep dive into a subject matter, and you believe that there’s a recency bias, whether it’s wildly bullish or wildly bearish, I love the deeply cyclical extremes because it’s there where you can find the most interesting investment opportunities.

To me, I’m not interested, none, zero, in buying what the crowd is buying, or investing in the markets where from valuation standpoint, I don’t know, is it in the 95th percentile where we’re stretched? I like things where people have run away from, have hated it, have shat all over it because they think that there’s nothing left. Obviously uranium’s one of those. But to me, that’s where you’re going to find your most interesting ideas, and with the greatest risk reward. And I think about, to me, all the rest is noise, and that’s why when you think about … and I struggle with the podcast sometimes because I can’t keep repeating myself on stuff like that, but a lot of times the best thing to do is nothing.

If you’ve done analysis, you’ve done work, you’ve come up with a variant perception or view on something, all the rest is noise. You don’t always know when something is going to turn, but if you have valuation support, and if you’re a growth investor, a momentum investor, you will get no value out of listening to this podcast. None. Zero. You’re going to go off and try and find a thing that’s constantly growing and is ripping to the upside and is beating numbers. That’s great. That’s not what I do, and if you’re listening to this, you’re not going to get a value if you’re hoping to learn about that.

The way I view investing is, I’m looking for something that has significant upside, and if I’m wrong, had limited downside. So I’m looking at risk reward. And then I let time arbitrage. I arbitrage time. I don’t know if something’s six months, a year, a year and a half, two years, but if I look at something that I think has, I don’t know, five X upside, and let’s say, or let’s say 500% upside and maybe 30% downside. I can’t get that investing in the across industries in a regular … portfolios don’t exist like that. Pick an industry. I don’t know. Pick three times upside, two times upside. Whatever industry you’re looking at where there’s asymmetry.

And then you let patience, and once you’ve done your work and you’ve identified some catalysts, and a lot of times a catalyst, there will be a catalyst you hadn’t thought of, but if you have valuation support on your side, sometimes it just gets on the long side. Some things just get so washed out that bad news is good news. I think about when I started talking about uranium publicly, in I think the spring or summer of ’17, probably the spring. Price of uranium I think was 23 bucks. Today it’s 25. Cameco is probably the same price. Cameco is maybe a little bit more now. The URA, the ETF, that’s down, but that’s a different ETF than it was then. Now it’s gone from 100% junior miners to 40% junior miners, and they have a bunch of other hodgepodge of nuclear power components in there. It’s caused a mass selloff in the ETF, so it’s technical, it’s not fundamental.

But a lot of the names, they’ve done whatever. That’s a gift from the investing gods. When I think about the upside I have, which is multiples and multiples versus, I don’t know, flat, down 10 percent since then, not the price of the commodity. Fundamentals keep changing, keep improving. Replace uranium with anything you’re looking at, whether it’s offshore drilling or shipping, stuff like that. Right now that’s really out of favor, until you think about it. That’s how you make huge money, when no one else is there, you’re playing at a field where people … you’re early, you’ve done your work, and if you’re right, that’s how you get huge payoffs. If you’re wrong, you won’t. That’s the market. But it got me thinking.

And so a lot of the people I like to pay attention to are not necessarily professional investors. They’re investors that I’ve stumbled across. They’re people who are not professional investors, that are just folks with a view. And I think that’s really cool, because you could constantly be learning from people’s different opinions and how they think about things. And one of the guys that I think is kind of interesting and has a very interesting view on being a contrarian investor is somebody that has been on Twitter and I’ve seen once in a while, and I’ve seen some of his videos, and I think kind of has an interesting perspective on things, and we’re going to bring him on today to talk about … it’s not what he does for a living. He’s not an investor. He happens to be in the power industry, and he happens to be an investor in uranium, but we’re going to talk about other stuff and how he thinks about it.

So from one contrarian investor to another, and I keep saying … the word contrarian, I think that gets overplayed. I’m a contrarian. I mean, what are you? You’re antithetical? You’re a non-conformist? Whatever it might be. But we’re going to bring him on now, and just kind of talk about how we think about it. So John Polomny, welcome to the podcast.

John Polomny: Thanks for having me. Appreciate it.

Mike Alkin: So you’re a Texan, as I read on your website. I lived in Dallas for a few years, so I’m a big fan of Texas. And I have to say, [inaudible 00:27:08] people. I really enjoyed living there. And you’re in the power industry. Tell listeners, give a little background. tell them who you are and what you do.

John Polomny: Well, when I first left high school, I had the opportunity to go to college, but I chose not to. Instead I took an opportunity to go to the US Navy, and I just wanted to kind of travel. That was my main thing, kind of get out of the smaller town that I was in. And I was fortunate that I got into one of the engineering ratings. I wasn’t a trained electrician. And then I’ve had the opportunity to be on various ships, travel around the world. But then later in my career, I got into ship building and working at Pearl Harbor Naval Station and working on nuclear submarines in a maintenance capacity for three years. And-

Mike Alkin: That’s pretty cool.

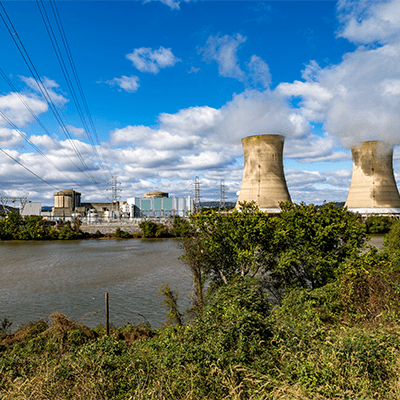

John Polomny: After I got out of the service, I got into the power industry as just a ground floor operator, and was able to work my way up. I worked for two major utilities. I got into operations and maintenance, and eventually became a plant manager, and then wanted to broaden my horizons and moved on to project management and construction, which is what I do now. So I’ve worked on just about all types of power plants. Nuclear, gas fire, coal fire, and now I’m in doing renewable construction. So I think I’ve had a fascination with energy as I’ve gotten older and more well read and educated. I mean, I think people really take for granted the energy industry and energy in general, and they don’t understand how energy from all forms, how it underpins our modern lifestyle. So I’m kind of lucky that I got into something I’m really interested in, and it’s a focus for my investing. I’ve spent a lot of time looking at energy, oil and gas, power production and things of that nature. So that’s kind of my brief [inaudible 00:29:33] synopsis of my career.

Mike Alkin: Now John, you and I have never spoken before. So you have no idea what I said in the preamble to this. I was talking about … and I didn’t know … I knew you worked in the power industry just from your website, and I didn’t know you were going to give me that background. I just in the preamble talked about how, for investing, how I think it’s completely not necessary for having a finance degree, for being college educated, for any of the … needing an MBA, needing a, none of it is necessary. And I talked about my nephew, who is going to trade school to be a plumber. And I was talking about all the opportunities that exist for him, and who knows where it’s going to take him, but he has a trade.

And as I’m listening to you speak, I’m smiling because I had just talked about that. And the other thing you just said, that as I’ve gotten older, and energy has played a more important role in my thinking, and throughout my career, I worked for two hedge funds that had a focus on … not pure focus, but a heavy emphasis on energy investing, in oil and gas and other stuff. And energy to me is everything. I mean, and you just said it. We take for granted when we turn those lights on, we take for granted when we put that TV on, what’s there, and forget the infrastructure that’s required to make that happen and where it all comes from.

And I’ve been reading and reading and reading the last several years, and you just realize what a monumental task it is to get those lights on and get that TV working and to keep that refrigerator cooled. And there’s a billion plus people around the world who don’t have that. So you bring a really, really interesting perspective. So as you talk, you’ve done, you said these different facets of it. What have you learned from doing coal, doing renewables, doing natural gas, doing nuclear? Talk to us about that, as the evolution of these different power sources.

John Polomny: So I think one of the main things that I’ve talked about that really strikes me, and which I think is pertinent to this whole discussion around renewables and the selection of energy fuels and sources, I think people have this misconception of energy evolution. It’s really something that I talked about in a video a couple of months ago. I brought up, you can go to the Netherlands and you can see windmills there that were built in the 16th, 17th century when the Dutch were reclaiming land from the sea, and they used wind and water pumps powered by wind to help them reclaim parts of their land.

And subsequent to that, when you got to the 19th century and James Watt when the steam engine was invented, the reason why we transitioned from using those windmills and they went to steam driven pumps, you can read the history of this, is because the steam driven, coal fired pumps were more efficient. They could do more work. And I think what people don’t understand and what really strikes me when you’re talking about energy is, the reason why coal was used and is so prevalent is because it’s a very dense, easily accessible, plentiful and cheap, full of power. And what we’ve seen through the history of man, the biggest trend in the history of the world is the [inaudible 00:33:38] man and his transition from less dense energy sources to more dense energy sources.

When we were hunter gatherers, we would use whatever scrap wood we could find or dried animal dung, and the Bedouins still use that in North Africa. When they’re traveling, they use animal dung for fuel. So as we discovered coal and went to the Industrial Revolution, coal was the fuel, it was the antecedent, it was the enabler of the Industrial Revolution. And then came along with adverse effects. It is polluting, particularly [inaudible 00:34:15] burning coal. There’s ash that’s left over, the constituents of coal sometimes are not very good. They have heavy metals in them. People can see in the news right now in North Carolina, Duke Energies, and the discussions with the state about how they’re going to deal with all these ash [inaudible 00:34:33] that have been left over from the burning of coal and how that’s going to be dealt with.

So I think that what struck me is, we went from less dense energy to more dense. And I have not ever seen a country or any type of civilization, if you will, that has advanced to a more dense energy fuel and then regressed to a less dense energy fuel. So it kind of strikes me that the zeitgeist nowadays is this view that quite a few people have … and I understand the view. Mike Shallenberger’s talked about this. You’ve had him on the show. And this view that we’re just going to have this utopian society and it’s going to be sun and wind, and there’s not going to be any pollution. I mean, it’s kind of ridiculous, because what it indicates to me is just, it’s what I call, people are not educated. I don’t want to use the pejorative and say stupid, but what I say stupid is, not understanding the consequences of a current decision.

And the reason we use coal and oil and these things is not because people are fat cats sitting up at Exxon. It’s because they’re cheap, plentiful, and they’re very highly energy dense, and they allow us to do work that enable civilization. And I don’t think that’s hyperbole to make a statement like that. So I think that’s the main thing that’s really struck me and what has led me to really look at energy. I mean, just as a quick segue, when Jay Leno has The Tonight Show, he used to do this segment called Jay Walking, and he would go out into the street and ask the average man questions like, where does bread come from? And people would say stuff like, from the grocery store. Where does electricity come from? The plug in the wall.

I mean, I don’t fault people because it’s very complex. When you’re sitting there at Christmas morning opening presents with your family and the lights are twinkling and the heat’s on, I mean there’s men and women that are at power plants or at gas transmission stations or wherever, providing these materials to people. And it’s a lot of investments, hundreds of billions of dollars, trillion dollar industries, with a lot of people involved 24/7, 365. I had a talk one time with a very liberal friend who just doesn’t get it. He doesn’t understand why I don’t understand. And I said, “Listen.” I’ll just say his name is Joe. That’s not his name, but just …

Anyways, I said, “Go to your disconnect at your breaker on your house on Friday afternoon when you get home, and open the disconnect. Cut the electricity off to your house for the weekend and see how 80% of the rest of the world lives. Because I’ve traveled extensively and I’ve been to the third world and second world countries and worked in them, and it’s really amazing what happens when the electricity just goes off when you’re in the middle of a pass. Or the water is turned off because the pumping stations don’t have power, so you have no water, you can’t take a shower. I mean, these little things that we take for granted, and then understanding that it’s not about a bunch of fat cats trying to get rich at the expense of your children’s lungs, it’s that we’ve made a decision that certain energy sources allow us to do things that make our life better. So that’s kind of my … it’s kind of long winded, I know, but that’s kind of what my thinking has evolved over time.

Mike Alkin: No, you weren’t long winded at all. You were very insightful. And you mentioned the dense versus less dense, and one of the things when I first started four years ago or so really trying to understand the nuclear power story, because yeah, as a layperson who didn’t understand at the time really uranium or nuclear power industry, I wanted to understand nuclear’s role versus wind and solar. One of the things as a short seller over the years, somewhere along the way we had looked at wind and solar component makers and when they were trading at ridiculous valuations. And we were attracted to that, but it was years ago, and it seems to be there’s this argument of it’s either or.

And for those who are anti-nuclear power, there’s just no changing their mind it seems. But there’s this view that, well wind and solars going to replace everything. And it’s just, as I endeavor to learn about it and I started learning and peeling the onion back, I realized, there is a nice role for wind and solar, but it’s a complement to nuclear. It’s not going to replace nuclear as a cleaner energy source. You mentioned less dense. Can you talk about why that matters when we’re thinking about electricity generation?

John Polomny: So for example, I mean I don’t have the exact stat … I think Shallenberger mentioned this once when he was on your show, but let’s just look at from this perspective of like when you’re talking about nuclear power vis-a-vis coal or even natural gas. So I mean, the amount of … nuclear fuel is so dense that one pound of … and people can do their own research on this, but one pound of uranium can supply the equivalent of tons and tons of coal or barrels and barrels of oil, and it’s the same thing. It has that advantage that the energy content of the material is so dense and it provides so much energy, it’s also a net benefit just for the fact of evening the waste stream. I mean you could take all of the nuclear waste that’s been generated by these plants over time, and it fits in the space of a couple of football fields.

I think people overlook these things. People don’t understand the tremendous amount of land that’s required … I’ve been on an actual oil and gas drilling site. I’ve seen what happens. I’ve seen the water that’s needed. I’ve seen the intensity on the roads in areas of Texas where it’s very rural, [inaudible 00:40:45] for example. And when that was booming, you couldn’t even get through there. It just was amazing the amount of activity, the amount of people, the amount of equipment it took to extract that energy. And then you could say the same. I’ve been to wind farms in Wyoming where the next property over had an [inaudible 00:41:04] uranium mine where they were using [inaudible 00:41:07] process, and you didn’t even know there was a uranium mine there unless you knew what the well vents looked like.

And it was unobtrusive, you didn’t notice it, it’s a controlled, very highly dense process. And I think with wind and solar, I mean you can put a nuclear plant on a facility on a small amount of acreage, and the equivalent amount of wind or solar you would be talking about tens of thousands of acres to get the same amount of power. And [crosstalk 00:41:40] nuclear. I mean, sorry, go ahead.

Mike Alkin: Yeah, I was going to say, John, the European Nuclear Society puts out a good start on that. They talk about the differences, and they say eight kilowatt hours of heat can be generated from one kilogram of coal, approximately 12 kilowatt hours from one kilogram of mineral oil, and 24 million kilowatt hours from one kilogram of uranium, just to put that in context, I mean the difference in the density of nuclear power.

John Polomny: Exactly. And the point is, is that you can go on the EIA’s website, you can go look all these numbers up. And I think some of the problem is, is that people have a problem with large numbers, and when I talk about it sometimes, sometimes I use a lot of … I’m a little sarcastic in some of my videos. But basically the United States consumes about 95 quadrillion BCUs. Quadrillion. I don’t even know [crosstalk 00:42:39]

Mike Alkin: Quadrillion, yeah.

John Polomny: Yeah, that’s a lot of euros. I don’t know how many, but it’s a lot, to the point where you need a scientific calculator to make some of the calculations. But anyways, you have to get those BCUs somewhere. And to your point, yes there is a role for solar and wind. There is a role for natural gas. In fact, just as a side note, I mean people need to note something. Notice how you see a lot of the major oil and gas companies, I’m not talking about [inaudible 00:43:12], but the larger ones are very interested in promoting renewables. They really like wind, and why is that? They like wind. I mean you could say it’s green [inaudible 00:43:21] or something, but also when you have wind energy and being so diffuse and often intermittent, you require a backup source to operate when the wind is not blowing or the sun is not shining, and that’s typically our natural gas peaking plants.

You won’t even notice these things. You’ll be driving down the freeway and you’ll see this little, couple boxes with a little smoke stack, and this thing is just remotely operated. When the wind turns off, the system operator or the guy at the control center for the utility will push a button, and that thing will come online in about five minutes and start producing power at an extreme amount of cost, by the way, and then they’ll shut it off when the wind … so I think it’s interesting that, what it is, is when you start talking about these large numbers and these things, I think people really don’t understand the whole process and understand how these things are produced in the large numbers that you’re dealing with.

And when you’re talking about nuclear and it being so dense and the amount of energy consuming just one pound of uranium, I mean it makes sense that it should be part, and it is part of our energy mix. I mean a large industrial, technology country like the United States with a 22 trillion dollar economy should diversify its fuel sources. It should not be reliant on one fuel source and one power production methodology. But having said that, things need to be approached from a logical, thoughtful, and a temperate point of view instead of just these extreme views one way or another. So I think the public, it’s typical. I kind of like this movie Tommy Boy, this guy and this character that Dan Aykroyd plays, Ray Zalinsky, the auto parts [inaudible 00:45:15], and in his commercials he makes auto parts for the American worker, and he’s one of those guys.

But in real life, he tells Tommy Boy, “You don’t seem like the kind of guy on your commercial, because hey look, what the American people don’t know makes them the American people.” And that’s not a slight, that’s not a pejorative, but it’s kind of true. I mean people are wrapped up in their lives. They have kids, they’re living a nice life. They’re like look, who doesn’t want clean air? Who doesn’t want clean water? Of course you do. I mean, you’d have to be a sociopath if you didn’t say that. But what does it take to get there? What’s possible and what’s the cost? What’s the cost benefit analysis? So I think at least in the United States and Western Europe, that conversation doesn’t happen. We just have these emotional appeals to the earth’s going to end in 12 years if we don’t do this, which is nonsense, and that’s the basis of the discussion.

We’re forced to have the discussion from that starting point, so that’s not helpful.

Mike Alkin: Oh, yeah no, it’s a great point, John. I could not agree with you more. One of the things you were talking about, the heat generation, let’s talk about the, to generate 45,000 kilowatt hours of electricity is 10,000 KGs of mineral oil, 14,000 KGs of coal, and one kilogram of uranium. I mean, so when you talk about density, it’s just unbelievable the difference. But to your point, you’re right. What the American people don’t know, that’s an interesting line, because they just want what they want, and they expect it there. And to your point earlier about traveling around the world, it’s not normal what we have and what Western Europe has. I mean, we take for granted all of the energy reliability that we have.

And when I think about the growth of nuclear power, it’s not happening in the US. It’s not happening in Western Europe. It’s happening in the emerging markets. It’s happening in Asia. It’s happening in the Middle East. It’s happening in parts of the world that are becoming more urbanized, and it’s fascinating. So let’s shift gears for a second. Talk about how your interest in your career, in energy and power, how that translated into you becoming a thoughtful, deep value, contrarian investor with an opinion, and coming out and talking about it to other people. How did that metamorphosis occur?

John Polomny: So I’m going to give you the cliché. I mean, I started messing around, I remember back in ’81, ’82, I was probably 11 or 12 years old, and my dad used to mess around. My dad was a fire fighter, career fire fighter in Minneapolis Fire Department, but these guys were always dabbling in something, commodities or junior mining stocks, all kinds of stuff like this. And I think it’s more for entertainment than actually trying to make money, because I don’t really remember too many guys making money. But anyways, my dad used to get the Wall Street Journal and Barron’s, and when I [inaudible 00:48:14], I would run off to the mailbox and read … I didn’t know what I was looking at, but [inaudible 00:48:21] I had an interest.

And one of the things that he was into was technical analysis, point and figures specifically, and he had a big book about point and figure charting. So I just took it upon myself. I read this book when I was like 12 years old, and I’m like yeah, I’m going to double tops and triple tops and double bottoms and all these reversals and all these things. And I started making my own charts with graph paper, and I didn’t have any money, I was just playing around, and this was right when the market took off when Volcker was … in ’82, ’83 when Volcker started lowering interest rates, and we had this big stock market boom. And you probably remember that time.

Mike Alkin: Yep. Yep.

John Polomny: And so the problem, at this time it was like ’85 when I started getting into high school. After high school, I got into the Navy and I was school in the Navy, and I was still doing the point and figure. I actually had some money, and it wasn’t like nowadays. I like telling this story. There were no cell phones, there was no computers, there was no smartphones. I mean I used Uriel [inaudible 00:49:23] Brokerage, he was a discount broker, and I was trading options based on my point and figure charting. And the worst thing that could happen to me happened. I actually had early success, and it was really the bull market that we were in that was raising all [inaudible 00:49:42]. And once you have early success, you actually think you know what you’re doing. And I was taught very quickly that I didn’t know. When I lost, I had an account maybe five or six thousand, $10,000, and I lost everything. And so [crosstalk 00:49:56]

Mike Alkin: No better teacher.

John Polomny: Yeah, exactly. People talk about, well you should pay for trade. No, you should use real money because you will feel the full emotions and that sucked out feeling in your gut when these positions go against you. So after that, I started doing what most people do. I read Peter Lynch’s book One Up On Wall Street, Marty Zweig’s book. I started going to libraries, and they had the old value line, the thing [inaudible 00:50:23] two New York City phone books. Every week the new add on would come and was a new update to the company. And I started researching things.

And what I did was, I saw a commercial on the S&N about drift investing. And I forget the name of the [inaudible 00:50:39], but they would send you this book, because nothing was computerized back then, which had all of the companies that had dividend reinvestment plans. And I said look, I’m in the Navy, I’m traveling around, I really don’t have time to do this. So what I’m going to do is just set up some drift programs with some good companies like McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, this kind of stuff. So that’s how I kind of started out. And I did fairly well. I built big positions in these big blue chips that pay dividends. It was kind of like a pseudo Warren Buffet methodology, but I didn’t really know what I was doing.

Mike Alkin: Yeah, sure.

John Polomny: But built myself a little index on it, if you will. But then what happens is, is that that’s boring, and we as humans, a lot of times don’t like boring and certainty, we like to gamble. And I think this is kind of a good shout out I want to give to a guy that changed my thinking on this stuff, is a guy named Meb Faber. I think you should try to have him on this show, he’s excellent. But his podcast and his writings really changed my views on … he talks a lot about this, the human psyche, about investing and speculating, and really this gambling mentality that a lot of people have.

And I think I kind of noticed that, because my returns some years would be good. What I started doing is started getting outside my lane. This is around 2000, the tech bubble. And I didn’t get sucked into that, but I tried to go short. I could see what was happening in the bubble, but I didn’t, there was really no … I didn’t have any rules. I didn’t have a plan. And so my results were not consistent, if you will. It was hit and miss. So finally, I was doing my taxes one year and I said, I’ve lost like 10 grand this year, and the previous year I had made a certain, good amount of money. I’m like, why can’t I get consistent like these other investors? It seems like I can figure out these industries or things, what am I doing wrong?

And one of the things that Meb talks about is, you have to really have an investment plan. You have to have rules, and you should write these things down. And what I did was, I started reading Warren Buffet, but then I got more attracted to his partner, Charlie Munger. And I think Charlie Munger’s really the brains behind the operation. I mean Warren’s a good guy and he knows a lot, but Charlie Munger is really, really a wealth of information. I mean, I encourage anybody that wants to be an investor or speculator, or just general life knowledge, to get online and just watch … he gives talks all the time. He’s free with his knowledge.

And some of the things he says are just, they’re just common sense. I mean, one of the things that stuck in my mind, he was talking about … he’s a big fan of the former prime minister of Singapore. He really talks a lot about Singapore and how it’s one of the models of capitalism, and he’s a big fan of Lee Kuan Yew. And he said, “Figure out what works and do it.” And so that’s what I said to myself. These successful investors, we know who they are, I’m going to go read about them and find out how they’re successful. And then I started putting together rules and a plan and how I would conduct myself.

And let me just go out and say this, and I’m going to tell you something provocative and I think a lot of people aren’t going to like. I think to the average person, the average investor, if you will, retail investor I’m talking about here, the best plan of action for this person is to understand compounding and time preference, and basically use their tax advantaged retirement plan or an IRA and just put a sane amount of money into an S&P index fund for 30 or 40 years and they’ll be just fine. That’s what most people should do. And if you don’t have, if you’re out there with 5,000 in an account, you think you’re going to trade or you’re going to be an investor or speculator, it’s going to be difficult to do.

You’re not capitalized properly, your knowledge base. So I encourage most people that I talk to that ask me for advice, because that’s what they should do, but they’re not going to do that, Mike, as you well know. They want to be involved. They want to gamble. I mean you get a dopamine release. I’ve done research on this. When you’re gambling in Atlantic City or Vegas, you’re hitting your pleasure centers. It’s the same thing when you’re trading and when you’re buying a stock that goes up, or bitcoin when you had that. I mean, this is what happens. It’s psychological. It’s biological.

So what I determined was, I have to have rules. So I started reading all these smart guys. Howard Marks, Warren Buffet, Charlie Munger. I can go down the list. [inaudible], all of them. And what I started realizing, is a common theme is that your results, more often than not, are mostly going to be effective based on the price you pay for that particular asset. If you overpay for stocks, for example, like we’re in a position right now in the stock market where we are at all-time highs in every valuation metric you can look at. Now, history tells us that our 10 year forward returns are probably not going to be that great.

That’s no guarantee. We could go on to make even further highs and get more over value, but if you’re buying stocks at these levels and just general stocks, your returns over the next five to 10 years are probably not going to be that great, and you’re probably going to see a major draw down of 50 or 60 something percent, something like this, 40, 50 percent, and you know what’s going to happen? Most of these retail investors will sell out, and they will never touch the market again, and they will miss out on the compounding and the wealth creation as we go on. So what I did, is I created rules. I looked at these successful people. Another Munger quote that I like is that he says that he believes in the discipline of mastering the best that other people have ever figured out.

I don’t believe in just sitting down and trying to dream it all up myself. Nobody’s that smart, and that’s exactly right. So I think that’s kind of how my evolution came. I wanted to get more consistent. I had success, then I would give it all back. I’d have success, I would give half of it back. And then I started realizing look, how to not lose money, how to value things properly, how to understand market sentiment, and how all these things are a latticework that all fits together for a speculation or an investment that you’re making. And it took time. It took a lot of soul searching. And the thing that really motivates me right now is, I want to get that word out. I want to talk to other people about that, because I’m in my early 50s, and I learned a lot of these things late in my investing career.

Like I said earlier, I started out when I was a teenager, but I didn’t know anything. And I gave up probably 15, 20 years, 25 years of not doing things correctly, and that’s a lot of time that could have been used for compounding. I mean, I’m in a good spot now, but it could have been even better. So I think that’s one of my main goals. I want to get out there, I want to tell people my story, I want to try to educate them, and I want them to understand that you can use these markets. If you use them correctly, they can create a tremendous amount of wealth for you over time if you understand how it works and what you’re doing.

Mike Alkin: Fabulous discussion there, John, or points you make. I had the benefit of having Marty Zweig as my direct boss early in my career. You mentioned Marty Zweig. And he and Joe DiMenna at the firm of Zweig DiMenna. And for those of you who are a little bit younger, Marty Zweig was one of the regulars. He was an economist, and often quotes in the press, and he was a regular on Louis Rukeyser’s Wall Street Week, which for decades was a TV mainstay on Friday nights on PBS. And you mentioned rules, and that was one of the things, that’s why DiMenna is Joe who ran the portfolio and Marty was the macro guy.

And it’s having a set of rules, which I to this day keep on my desk of the rules of investing that are important. And some of it is finance stuff, but a lot of it is the art of investing, and it’s about how to think about it, how to look at things. And I saw on your website, you have the magazine cover indicator, which you published on April 18th. And one of Marty’s great things was, if it shows up on two covers of national magazines. Now, folks who are listening who are younger, if you’re a millennial you might not even know what a magazine is, because you read everything online.

But if Business Week or Barron’s had it, and they were talking about how great it was, it was time to get out. And that was Marty’s famous saying, is all about that. And you talk about learning, and the thing, John, that I see people do more than anything, is they try and do too much. So much of investing over my career, I’ve learned in the big winners, especially as a deep value investor and a contrarian investor, is time arbitrage. Doing your work, doing your analysis, if you are a very into perception, is worthy of being attached to an asymmetrical risk reward, then you’re early by definition. You are seeing something that the market has not seen.

Now, you’re not going to know when it turns. Nobody is going to be able to say, “Here is the day the catalyst occurs.” Timing is the hardest part of it. But if from a risk reward scenario, that your downside is de minimis compared to your upside, let time work in your favor. And it’s one of the things I see. I use Twitter as a barometer. Some smart people and really learning, but anxious and wanting to see it yesterday. From my perspective, I don’t like to play in the main market, meaning regular names that are part of the indexes, because for me, I was saying earlier before you came on, you’re playing in a 95th percentile right now of valuation, and to me that’s not interesting, and I can’t figure out, I’m not going to beat the market. Who’s going to beat the market?

I could beat a segment of the market, but I can’t beat the market. And that’s why I … but when you find that and you’ve done that work, whether it’s shipping, whether it is offshore drillers, whether it is offshore service companies, whether it’s uranium, once you have that fundamental analysis done and you feel comfortable with … you gotta maintain it, but don’t get drawn into all the noise. And at some point in time in the future, it could be a year, two years, three, whatever that is in the future, when you’re at a barbecue and everyone’s telling, I use idea dinners as my thing, because my hedge fund buddies, when I’m sitting at an idea lunch or a dinner with seven or eight other hedge fund guys, who right now, a year ago weren’t saying a word to me about uranium, or two years ago, and now I’m getting inbound calls.

When they start telling me that … when five of those seven guys or eight guys are saying how great uranium is, that’s the time you want to start to say, uh oh. It’s starting to get too mainstream. Those are your magazine cover indicators, if you will. So much of investing is art versus science, and the science being the finance part of it. And I always say, there’s not much more than fourth grade math that goes into analyzing companies. If you could add, subtract, divide, and multiply, and put a little bit of logic behind it and recognize patterns, there’s a lot you can do. So it’s great. Another thing too, I had the great benefit of working for another guy who is a deep value investor with a hedge fund for gosh, almost 30 years, David Knott, and you would see David and times of, when the market was really volatile, extremely volatile, and David [inaudible 01:03:05] spectacular over the years.

And I was a partner at his firm, and what you would see was, in the most stressful and most volatile times, was he was the calmest, never reacted, didn’t get shaken out, relied on the fundamentals. And I think that’s so important for people, not to be emotional when they’re investing, and I think that’s a thing that people get caught up in a lot, is the emotion of the investment. Especially now, with all the information sources that are out there, whether it’s Twitter, whether it’s CNBC, whether it’s Bloomberg, whether it’s these websites with all these chat rooms, it can be overbearing, and I think people have to just remain disciplined to it. And it starts, going back to what you said, have a set of rules for investing, keep them on your desk and keep looking at them, because it’s so important. Really good point. So talk to listeners about … from a contrarian or not, but I know you’re a contrarian investor, but what you’re finding interesting right now.

John Polomny: So my largest position, and I don’t want to glom onto what you said, but I’ve heard you say in some of your talks, uranium right now, to me, just because I understand the fundamentals and it looks like … now I participated in the last run up, and I saw what can happen when a uranium bull market gets going. And I’m not suggesting that this particular … no one can tell the future, but what I’m saying is, to your point what you said earlier on the waiting, this is the thing I try to stress to people. Uranium to me, just on the supply demand dynamics, which you went over and many other people went over at ad nauseum, the fundamentals are so great that I think what people don’t understand, one of the things that [inaudible 01:04:54] real quick to the cyclical commodity basis.

One of my other heroes is Rick Rule, and there’s another guy that people are going to be involved in these type of deep cyclical commodity type businesses, which a lot of these things that we’re talking about are, they go in very, very well defined cycles that you can track and predict. There is a company called Altius Minerals and it’s run by a guy named Brian Dalton. I think that he is one of the smartest resource based investors in the history. I’ve followed this company for 10 or 15 years, and that is how their entire business model works. They understand the cyclicality of these businesses, they understand the long investment lead times, which causes and contributes to the cyclicality, and they have mapped this out.

And same thing with Rule and some of his cohorts. You get involved in these things when they are completely bombed out. I had a guy write me the other day. He was despondent because he said he’s been holding gold shares for the last eight years, and he’s lost all his money. Right off the bat, you can’t hold, these are not buy and hold investments. These are not. These are speculations. We are speculating on what we think is going to happen in the future. Now, we are taking calculated risks based on our analysis and fundamentals, but you can’t buy and hold these things for decades like you can some rope stock or some blue chip stock in a Widow and Orphans fund. These are, as Doug Casey describes, a lot of these companies are burning matches.

They have no revenues. They have no way of generating any kind of cash flow. So they’re reliant on share issuances and telling stories and doing things. Now, when the cycle changes in a lot of these industries, a tremendous amount of money from generalist funds flows in, and you get a tremendous run. I mean for example, you well know, in the previous bull market, I was talking about this uranium. I was following it before the last one got going. There was like three publicly traded uranium companies. They were Cameco, International Uranium, and I think that’s just when they bringing Paladin public. And there wasn’t anything there. At the height of the market when the market cap of the industry was 140 billion dollars, there were 500 publicly traded uranium companies at the peak of the last cycle.

How many top of the uranium teams actually existed in the world when there were 5,000 publicly traded uranium, or 500? There wasn’t. There was the same guys that had worked at Union Carbide and Kerr-McGee and [inaudible 01:07:37] and these other companies, and these are the things that people miss in some of these cyclical industries. [crosstalk 01:07:45] That’s really a key that people need to understand when we’re talking about these things.

Mike Alkin: Well I think too, and timing is always the hardest part, but I will say this. There is a way to identify catalysts that have a time element attached to it. For instance, pitching uranium in a bull market in 2014, 2015, even parts of 2016, and what could you have seen there? At that time what you would have seen was increasing production, increasing capital expenditures on building and exploration, and you would have seen no supply cuts. But for me, one of the most important things you wouldn’t have seen was a need for utilities to buy, because their uncovered demand wasn’t there. They didn’t have uncovered contracts coming up to marry to the fuel cycle.

So if you were looking at now, those contracts are rolling off, and they need to reenter contracting. And so what is that time period? That time period is, well, 20% is roughly in less than a couple years, and then you start to get up towards 75% as you go seven years out. If you look back at the last bull market when these stocks starting ripping, 405, they had no uncovered demand. Think about that. There was very little that was not under contract. So the stocks were anticipating it a couple years. Now when you look at the time cycle of the fuel cycle, it’s a couple of years. It’s 18 to 24 months. And you look at it now and you say, okay, what do you have now that you didn’t have in ’14, ’15, and ’16?

Back then the bull case well, Japan’s got to come back online. It does? Who said? There’s something called LNG. What you didn’t see, was in an over supplied market, you didn’t see disciplined spending. You didn’t see on capital expenditures, on exploration or drilling. You didn’t see supply discipline, and you had no uncovered needs. Whereas now, as you kind of think about it and say, well, do they have to buy uranium if security of supply is a big deal? They kind of do because they have all these uncovered needs from a contracting standpoint. So while you can’t say, oh it’s tomorrow, it’s when does price discovery occur in a sector? Well, in the fourth quarter of 2017, there were some major requests for proposals from electric utilities in the market until January 18th of 2018 when section 232 was filed.

And so price discovery in the turn market, which is what matters, disappeared because they pulled it and said, “We’re going to wait and see how this whole thing plays out.” But if you’re comfortable in waiting, but you can identify some catalysts, and oftentimes too, John, I find this. It’s the catalyst you didn’t even expect that occurs, that you couldn’t have foreseen. Something happens. But if you had all your ducks lined up in a row, that tends to work that way. So it’s fascinating how you think. I could not agree more with most of what you said. What are you seeing right now that is of interest to you that listeners might want to take a look at from a deep value perspective?

John Polomny: So I do like the offshore service sector. It’s probably the worst oppression we’ve ever seen in offshore drilling and offshore service vessels. I don’t want to give any particular names, but [crosstalk 01:11:36]

Mike Alkin: Yeah yeah, no, that’s fine.

John Polomny: Yeah. I like that sector. There’s certain aspects of the shipping sector that are interesting, especially with the 2020 regulations coming for low sulfur fuel. See, this is some of the things we were talking about earlier. This is the second and third level thinking that you have to do. What are these catalysts? What are the things that are going to get these things off the [inaudible 01:12:02]? And I also like … I think people in the US are, especially in US and even Western Europe with some of my correspondents, people are too country specific. There are tremendous values around the world, and with the way things are set up now with ETFs and even getting on planes.

I mean, I’ll just give you a quick example of something I got involved with a couple years ago just from my network. I was able to buy a … I mean, people read my website, but I’ve had from Mongolia and [inaudible 01:12:34], I’m now starting up an account in Uzbekistan. These are places that are emerging now. And I’m not saying that you have to go to these places or get involved, but I bought an airport service company in Purgustan a couple years ago that was selling at about a PE of one at a 30% dividend yield. So these are some of the values that are out there, and these values even exist in our domestic markets.

Not that tremendous, but if you are willing to dig down deep, if you are willing to do research. Another example that people should look out for is, when a country gets bombed out like in Cypress in 2012 and 2013, the country wasn’t going to dry up and blow away. It goes through a deep drop, a market air drop, 99%, Mike. Cypress stock market dropped 99%. And the country wasn’t going to dry up and blow away. It’s a tourist based economy with this natural gas offshore optionality. And the EU stepped up. They got things squared away, and the country is one of the fastest growing countries in Europe now. It’s well on its way to recovery. The banking system’s curing itself.

And a lot of those stocks, I was fortunate enough to have a contact who was able to hook me up with a Cypriot brokerage firm, and some of those stocks are up three, 400%, and they were paying dividends throughout the entire crisis because a lot of them had offshore sales that weren’t tied to this Cypress market. So I think people need to make the world their oyster. There’s tremendous value out there, if you want to do the research. These deep cyclical things in the US and Canada run the resource markets, but you really need to understand that cyclicality. I like copper. I’m looking at some copper things going forward. And I’ve identified in my own newsletter a company that basically processes tailings from a large copper producer in Chile.

It has no exploration or production risks. They basically just pump water into these tailings, force the tailings into a plant, and extract the residual copper from the original leftover tailings. So there’s businesses out there like this, but I think you can find a tray of low valuations, give you optionality to a theme that you’re interested in that also give you some risk control. I’m not big anymore on doing junior mining investing. I think everybody that’s involved in this sector or wants to speculate in these types of sectors should really take a trip to Vancouver and go to one of the investment conferences. It’s very educational and eye opening, and it will really tell you what that whole industry is based on.

It’s not based on, for the most part, finding and extracting metals. It’s based on finding naïve people and extracting their money from them. So I think there’s tremendous opportunities, but I think you really need to do your research, and don’t be that guy like that emailed me and said we’ve been holding gold stocks for eight years and he’s lost tens of thousands of dollars. [crosstalk 01:15:42]

Mike Alkin: You would be deluded till kingdom come if you don’t find the right companies.

John Polomny: That’s exactly right. And I mean, I could tell the story of a guy named Darien Silmo who ran Silverado Mines for many years in Alaska, and that’s what he did. He made a 30 year career out of bringing some nuggets to Vancouver and Toronto, getting people excited, issuing shares. When he got his share count up to 300 or 400 million, he’d do a reverse split and start the process over with a new group of investors. So people need to be careful of what they’re doing. Here’s what I do. You got to write it down, why am I speculating, why am I invested in this particular sector, company, asset? If you use uranium, for example, you should have just listened to Mike Alkin or John Polomny or Doug Casey or [inaudible 01:16:28]. They said uranium’s going up, so I’m going to throw 10 grand at it because guys on Twitter said [inaudible 01:16:33].

What you need to do is, why am I putting my hard earned money that I earned by the sweat of my brow into this, and what is the reason I’m putting my money in here? What is the research I’ve done, and do I understand what’s going on here? And do I understand what the catalysts are that are going to create a sentiment change or a view in the market that’s going to push this asset higher? And if you can’t do that and if you can’t keep track of that and revisit that and do what I call, people that I talk with, which is called red teaming, which is taking the other side of it and poking holes in your thesis and trying to find where the issues are. You’re probably better off just putting 288 a payday into that index fund for 30 years, and go off and take your kids to a ballgame or go for a walk with your wife. That’s probably [crosstalk 01:17:22]

Mike Alkin: 100%, John. And if you just listen to me or listen to you and anyone else, when the going gets tough, you’re not going to have the conviction, and you’re going to probably sell at the wrong time. I see Twitter’s a great gauge, and I think I see some people, I talk about certain junior miners. I don’t opine at all, ever, on a company. And if I do, and I’ve cut back a lot, but if I do have a guest on the podcast that happens, I happen to own their stock in the fund, I will say it and I will preface it with, don’t own because I own it. You don’t know why I own it. You don’t know if it’s big or small at all. But I never will comment on a company.

But I look at some of the stuff, and you look at some of the management teams and what they’re saying, and you just say, ooh, buy or beware. And so because we’ve done the work on the companies, and we kind of know. And not to say that we’re not going to in certain companies get bagged, but we’ve done our due diligence and our best efforts. On a few of them, I mean you just never know. But you really have to, like you said, write it down, know why you own it, because it’s hard your hard earned money that you’re putting in there. And there is, I mean my God, so many of these junior miners are in business to raise capital. Not all, but … and raising capital isn’t a four letter word.

If they’re going into production and they’re doing project financing, 80/20 debt equity, they’re going to need it, it’s going to generate cash flow, know the valuation. Just somebody said to me over the weekend, well all these guys just dilute. Well yes, absolutely. A lot of them do. But they’re going to have to raise money when they go into production. Well, they might, but what does that mean towards its valuation? Factor that into it. And you have to dig deep on this stuff if you’re going to put your hard earned money into it. So how do people get a hold of you? [crosstalk 01:19:20] Oh I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to interrupt you. You were going to say something. I didn’t mean to interrupt.

John Polomny: Well one thing I think also that I think is very important when we’re dealing with these, especially resource companies, and I love the resource market, I’ve made a tremendous amount of money. But find out who the guys that are serially successful are and stick with those. I mean, there’s one out of 3,000 projects actually gets turned into a working mine. The mining business is a tremendously bad business to begin with. As Doug Casey says, I like to use this, it’s a 19th century choo choo training industry that sucks. The margins are horrible, the risks are high, and seek out guys like a Ross Beaty, who’s known as the broken slot machine. I mean, he’s created tremendous amount of value.

Look at guys like Frank Giustra. Look at guys like these various guys that have serially successfully done things. It’s the same thing in this uranium investing. Go to a conference. Pick up the phone and call the management team and say, “Who are the geologists on your staff and where do they come from?” I mean they might have old school guys from Union Carbide days, 60s and 70s. Those are the kind of things that you need to understand. You need to be in business with people that know what they’re doing and have serially successful resumes. Now that doesn’t guarantee that they’re going to be successful in their current project, but it helps separate the wheat from the chaff.

And when you’re dealing in these type of markets, you really need to limit your risks, and that’s one of the ways you do it. And believe me, it’s something to go to one of these conferences and talk to a billionaire that’s done this several times. These people make themselves available. They are interested in talking to people, and it’s just tremendous hearing some of the stories. I’m not going to get into specific stories, but I’ve been to dinner with some of these people, just happened to get invited. I’ve been invited to projects. It’s interesting, but tremendously shark infested water. So like I said, I think everybody that’s going to be involved in any type of these things compose themselves to go to one of these conferences at least once, just to get the atmosphere and understand what’s really going on. Because it’ll be interesting. You’ll go to every single booth, and everybody’s got a story to tell about how to get the unicorns and skittles to kingdom come. So it will definitely open your eyes.

Mike Alkin: Amen to that. How do people get a hold of you?

John Polomny: Yeah. So my website, I blog occasionally, is Actionable Intelligence Alert. I post ideas on there. I also am on YouTube. People can look me up there just by my name, John Polomny. I make weekly market updates, and then videos on different subject matter. And then on Twitter, @JohnPolomny. I think people should really, if you’re involved in these markets, get on Twitter. You don’t have to engage in conversation, but even lurking, you can really get a good sense of some of the really smart people that are out there [crosstalk 01:22:20]

Mike Alkin: And sentiment.

John Polomny: Yeah.

Mike Alkin: And it’s a good sentiment gauge too. [crosstalk 01:22:25]

John Polomny: You’re exactly right. You’re exactly right. So yeah, that’s the main ways to get a hold of me.

Mike Alkin: Good. I enjoyed talking with you. It was a lot of fun. Thank you for-

John Polomny: Well definitely appreciate it Mike. Yep, yep.

Mike Alkin: Yeah. And have fun out there on your power plant building stuff.

John Polomny: Right. Somebody’s got to do it. You got to keep the juice flowing.

Mike Alkin: I love it, man. Love it. All right. We’ll speak soon, John. Thanks again.

John Polomny: All right. Thank you.

Mike Alkin: Take care.

John Polomny: Bye.

Mike Alkin: Well, I hope you enjoyed the conversation with John Polomny. Interesting guy. Smart guy. I like a lot of what he had to say. I thought it was an interesting viewpoint, and he’s, we think quite generally as guys who are taking the other side of [inaudible 01:23:17] research and check lists and having a view on things. So for those of you who are waiting, Frank can’t make it on the podcast. Frank was going to come on, but he said, he texted me this morning said, “No need to have me on. I’ll come on some other time.” Frank was talking smack about uranium the other day on his podcast, so I was busting his chops over the weekend and we were going back and forth.

Frank and I are buddies, so I was letting it rip. And I said, “Let’s go, baby. Come on.” And he’s like, “Eh, I don’t … ” And he’s long term bullish, but he’s like, “Nah, don’t worry about it, you don’t have to have me on today, so I’ll come on another time.” So we’ll get him on another time and share his thoughts. I think he’s making more of a short term call based on sentiment and stuff like that, but we’ll just let that go. So anyway, hope you enjoyed listening with John, and I’ll be back next week. Talk to you later.

Announcer: The information presented on Talking Stocks over a Beer is the opinion of its host and guests. You should not base your investment decisions solely on this broadcast. Remember, it’s your money and your responsibility.

P.S. People are asking how I’m handling the NY Islanders’ traumatic exit from the NHL playoffs. Sigh… I’m ready to talk about it now.