Announcer:Free and clear of the chatter from Wall Street, you’re listening to Talking Stocks Over a Beer. Hosted by hedge fund veteran and newsletter writer Mike Alkin, who helps ordinary investors level the playing field against the pros, by bringing you market insights and interviews with corporate executives, and institutional investors. Mike sifts through all the noise of mainstream financial media and Wall Street, to help you focus on what really matters in the markets. And now, here’s your host, Mike Alkin.

Mike Alkin:It’s Monday, September 9 2019. Hope you had a good weekend. I love this time of year, my favorite time of year. We’re two weeks into the college football season, the NFL season kicked off yesterday. Hockey camps are opening, training camps, got the baseball playoffs sniffing around, right around the corner. In the air, you can smell the outdoor, the smoke from the fireplace is starting to kick in a little bit, those with outdoor. Wood burning stoves you can start to smell it a little. Just I mean, for me it’s sports Nirvana. kids go back to school. And of course my Mets, which I had mentioned all year, and I talked about the first half of the year how they collapsed. In the second half of the year they had the best record in baseball. And I debated a few weeks ago, do I say anything on the podcast? Do I even bring it up? Then I did and they faded since.

Of course they did, right? They reel you, they real you in, they reel in, and then they suck. So they’re starting to fade, they’re still four games back in a wild card, there’s still hope, they’re chasing the Cubbies. Cubbies had a tough weekend, Mets had a tough weekend last two to three at home to the Phillies. But, there’s still hope. And if you’re a New York sports fan, you know that you have such little hope most of the time. that if you have a little bit of hope, it’s a good thing. At least to be in the conversation. Now if you’re a New York Jets fan, the J- E- T- S Jets, you have just learned to live with disappointment. It’s part of your life, it’s part of the fabric of who you are. You’ve chosen that path to be just a suffering fan. This was supposed to be the year, and it may still be, that the hapless New York Jets led by second year quarterback Sam Donald, were supposed to have a pretty good year.

And because it’s New York, everything gets hyped. You talk to guys who played in NHL, NFL Major League Baseball. After a game the locker room and in New York has countless number of reporters radio, print, TV, they’re all over the place, in other cities not so much right? So everything gets hyped up here. The greatest city in the world, I promise you it’s not. Madison Square Garden, the world’s greatest arena, really? But it’s just a hype of New York. And, the Jets supposed to really you know, first year coach Adam Gase quarterback whisperer, that’s his label. Sam Donald, this is his year, second year the game slowed down for him, great. Jets were up 16 nothing yesterday. They’re down 17-16 with little under three minutes to go. Falling around 25, Sam’s moment to shine. Jets just lost 17-16. I mean, there were no drama, it went nowhere. I mean, you can’t make it up being a New York sports fan.

Anyway, back to school routine is here. I was pretty fired up last week. School started here for the kids but I was in London at the World Nuclear Association Conference, had other meetings when I was there. And my role is, I am the lunch maker. So got back into that routine, love it. You only have a short amount of time if you have kids, and if you know what I mean. I mean, the day to day the ho-hum. Sometimes it becomes ho-hum with the lunch making or the driving back and forth, going back and forth but man it’s awesome because you only have so much time, a little window snapshot, and then they’re off. They’re off to college, they’re off to wherever. So I really, I try and embrace it and I like it. So today I was back to my lunch making routine of course, taking my son’s phone away because he did something ridiculous to a sister which happens occasionally or said something ridiculous. So it was good, it was fresh right back into it after a long summer.

Making a lunch, grab the phone, say now the phone’s mine, then I’ll hide it, the whole routine, I’m sure if your parents you get it. But, and I also, when I was in London this past week, we talk about how, think about how complicated our press is and all the stuff that’s going on in the world and, man I got to tell you, I have some UK friends that I saw a lot and this Brexit stuff, and watching the BBC One over there, I mean, I watch it here too, but being there and watching what’s going on with Brexit and then trying to figure it out. And Boris Johnson his brother Joe, an MP, Member of Parliament over there, quit. Boris fired some people who didn’t want to fall in line. He wants to put a popular vote to the people in October, it’s proven to be very difficult, a lot of infighting going on, it was so complicated.

I watched an hour my first night there, got there Monday night in my hotel room, I said all right let me just catch up what’s going on here for an hour. And at the hour I was more confused than before. Then, had dinner with a friend of mine Tuesday night who is very politically savvy with family and parliament, and he said, “No problem I’ll explain it to you.” I said, great. We were lucky the restaurant was quiet. And he did a great job explaining it to me. And we just kind of laughed because we said it is confusing, isn’t it? So, you talk about uncertainty and on High Street, UK’s main street there’s a lot of unknowns. But, that’s here too. There’s a lot of stuff going on in the market, a lot of stuff with the Journal Today.

You talk about things that are precarious, WeWork weighs value under $20 billion for their IPO, and they’re supposed to go on a road show this week. WeWork right? The communal, go get an office, you don’t have to walk into big commitments, you could go and it’s a place where small businesses can go and hang their hat. SoftBank out of Japan invested earlier this year privately at a $47 billion valuation. And today they’re having a hard time getting it down at 20 to go in the IPO. I won’t get into the WeWork story maybe over time I will. But, and this is during time where the IPO market, they want companies that have cash flows. If you have a solid business plan and good cash flows, you’re not going to have problem going out. But that turns out this isn’t quite what people were thinking it might be. So it’s under pressure and you see Uber and Lyft, those IPOs gone smoke.

The goofy economy. So maybe the world is starting to think about that, that profits do matter. I was reading in the Journal, I kind of got my paper, Garrett my sound engineer’s probably going crazy because he hates the background noise but, we’re going to go with this Garrett. I was looking at the headlines, right? Rising global debt helps keep rates low. Debt owned by government, businesses and households around the globe is a 50% since the financial crisis to $246 trillion. And all that borrowing helped pull economies out of the nasty recession but, left them with high debt burdens, ha, no kidding. Mark Carney, governor Bank of England, “The world’s in a delicate equilibrium.” he said in a February speech. “The sustainability of debt burden depends on interest rates remaining low and global trade remaining low.” Well interest rates are remaining low. No doubt about that.

Negative yields. Another article here. There’s more than $16 trillion of bonds with negative yields worldwide. We got, all right. And most of them are sold in Europe, and originally offering positive yields. Most serious buyers of debt are the European pension funds and insurers, they need safe long term securities to offset all those big future liabilities. Then you see the US guys they’re pretty sharp. For those opportunistic US investors, their currency hedging their way into profits. So when an investor, a professional investor, or you can do it yourself if you have the wherewithal, they purchase assets in a currency of their own, they use derivatives to protect against the swings in the FX rates. Now, in this case though what they’re doing is, they’re using the hedges to squeeze gains from what look like losing bets, right negative yields.

So investors will use euros to buy the German 10 year government bond. So let’s say they hold the debt for three months, they may lose money on the investment like in theory, because the debt has a yield at -0.64%. But the way you make up for that loss, is you enter into an agreement with a bank to convert their euros back into dollars in three months. And the FX rate is determined by the gap between the US and European short term rates. So if you look back at last week, investors could convert $100 into 90.64 euros, using a spot exchange rate of 1.1032 per Euro. They could use that 90.64 Euro to buy 10 year bonds, with annual yield of -64%. Three months from now, if the bonds price remains the same, they’d be left with 90.50 Euro. But those are converted back into dollars at a pre-arranged forward rate of 1.111 per Euro. And in the end, the US investor who did that would be left with $100 and 55 cents for an annualized gain of 2.2%.

And that’s more than the roughly 1.6% yield on the US 10 year note. Now, you know this podcast is for regular investors, right? I don’t do this for professional investors. There’s an example of how stuff just eek out yield. Happens, right? It’s, there’s a lot of stuff going on in the world right now, people are looking to squeeze out returns. Bond investors, equity investors are nervous. You’re seeing the industrial outputs going down. All the uncertainty around the trade shenanigans going on, it’s causing cut backs to be cut back dramatically. You’re seeing corporations in industrial America, at least with all the uncertainty, cutting back spending. And some of those stocks who are dependent on that have had big moves over the last few years. So there’s a lot of uncertainty, a lot of a lot of risk in the market. You’ve heard me say it over and over again, [inaudible 00:14:25].

Think about it, so if you watch the news, you listen to the business radio, you read the newspapers, you listen to guys like me go on and on and on, I try not to do the macro stuff at all, or too much at all. But, it’s hard, right? You’ve had huge gains, if it’s in your IRA, okay, you could sell it, you’re not going to take the tax hit. But if it’s not, some people are reaching for yield, so they owe a lot to names because if they know the name, it’s a well-known company, pays a really nice dividend, rates are low. But what are you playing for? What’s the risk reward, and you’ve heard me say this price, or can hear me say it. Are you trying to eke out some more gains? So many things that influence the movement of the markets, the day to day movements.

That’s why, I’ve kind of morphed over the years into a very different style, where I look for things that aren’t in the paper. Things that nobody’s talking about. Things that are not priced for anything, for any level of success. And alongside I’m talking about, things where they don’t have to be great businesses, don’t have to be good businesses, they have to be mispriced businesses. Where, because of a lack of attention, because of recency bias, people have written them off. You hear me say this over and over again, right? Because I read the papers like you every day, and I talk to people throughout the investment world who have a good handle on this stuff. It’s hard. Earlier this year, it didn’t matter if you didn’t have profits, you’re a unicorn.

You came out, people got excited and just things changed. But, especially when you’re this long in the tooth in a market that’s gone up for 10 straight years, basically what are you playing for? What’s your risk reward? You’re playing for 10% upside? 20%? upside? What’s your downside if you get it wrong? If the market just rolls over to 20% down, I don’t know, 15, 30, pick a number. And I said this recently on a couple of podcasts ago, I think it was nice. What do you have here? You’ve got all these trade pressures, you’ve got CEOs who are afraid to spend, they don’t want to risk their business. If you’re in a consumer business really difficult to take pricing, that’s hard. I mean you hear bubble, bubble, bubble, people, the bubble talk, the bubble talk, I don’t know. A lot of people are trying to sell newspapers, newsletters, whatever to scare you.

I don’t know. I mean, student loans are through the roof, student debt, one over one, one and a quarter, one and a half trillion. Default rates are extremely high, auto loans at the bottom end, at the subprime or defaults are very high. Housing, that doesn’t seem to be too big of an issue but, you’ve got markets around the US at least where, and other parts of the world, Canada, Australia, we’ve got pockets that are just, prices are back to global financial crisis highs. But all this stuff, you don’t know what’s lurking out there. So again, what’s your upside downside? That’s a risk reward. So that’s why I like to look for asymmetry. Now with that, asymmetry takes time when you’re looking at things that are left for dead, that people have ignored, and most of them with good reason.

But sometimes you find an industry, a sector, or a company where there’s just, pricing is wrong. And you see a lot of times people say, price is the ultimate truth teller. I couldn’t disagree more, it is if it’s an efficient market, probably. In a market that has total transparency, and millions of eyeballs on it, and analyzing it, sure, it’s probably right. But not markets that have been left for dead. That’s where there’s not much, or especially in markets where been left for dead, and there is a narrative surrounding it that’s stale. And price isn’t the ultimate truth teller at any given point in time. So the biases that are in there, the recency biases that are in there, the lack of institutional investors paying attention to it. We’re talking about some industries and I see that in now shipping, the offshore services.

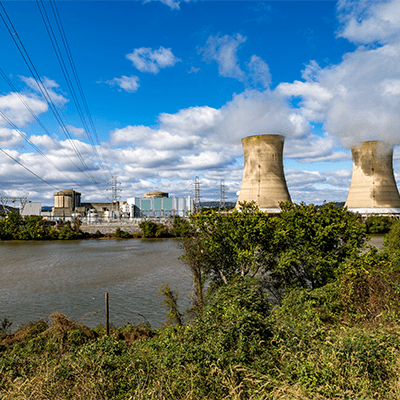

All the money that flowed into the shale plays. Look at the shale names are getting crushed. And it all looked down, and I’m not going to rehash all the stuff we talked about that. And obviously one you know near and dear to my heart is uranium. And so I was in in London this week for the World Nuclear Association meeting, it’s one of the governing bodies, governing, I don’t know if that’s the right word, but it’s the main Association for the nuclear fuel cycle. Made up of folks from the supply side, of enrichers, miners, converters, fabricators, countries that are building nuclear power, a lot of people there. And, this year it came out with its fuel report, every two years they put out a fuel report talking about supply demand, couple hundred pages.

And they do their presentations. And it was a very interesting meeting. And I’m going to bring in some of our guests right now we’re going to talk about it. Tim Chilleri who actually works for me. Some of you are on Twitter know him, he’s pretty vocal. So it’s kind of nice, because I don’t have to do a lot on Twitter because Twitter can be very time consuming. In the uranium world, they call him, there’s a large number of people who are quite passionate about it. And if I if I wanted to, I could spend all day long on that, talking with people who have some outlandish opinions, and you could tell by people, and I could tell, and Tim could tell and others can tell. When you take a piece of a mosaic and you use it as a thesis, that’s how you can get run over. And especially on the … You take the other side of something, and you can tell if people have done their work or not.

And, but again, you could spend all day on there, and I just don’t have the time or the interest to do it. But anyway, I’ll bring on Tim and we’re going to talk about London and go from there. Timothy Chilleri, what’s going on?

Timothy:Good to be here Mike, just back from London from the WNA last week and I got a good weekend’s rest, and ready to go again this week.

Mike Alkin:Good. Just so I’m going to preface this with saying that, I have an investment vehicle that is a, takes a very positive view towards uranium. So take anything I say with a grain of salt or same thing with Timothy, do your own research. Obviously, we have a view, and our view is positive. But we do spend our time, most of our time looking for where we are wrong. My historical background in the business in the industry has been as a short seller, so we come at this looking at it is, what’s the bear case and where are we wrong? But, I could be wrong, Tim could be wrong, it’s important to understand that. Obviously our view we’d like to think is unbiased but, these things creep in. So we’ll hopefully give you a framework for how to think about things, and just, I always like to say that when you’re here, if you see we own a company, if you see that we’ve invested in something it does not mean you should own it.

You have no idea why we may own it. You have no idea what purpose we own something for. If we did a financing or not, it’s very important to do your own analysis, do your own work. This is just more we do these things for educational purposes. So, that’s why we don’t pitch names, we don’t talk our book, publicly I’m pleased to talk about, no problem talking about the macro uranium but go out and find your own research so that you understand, where it comes from. So, anyway, so I … This was Tim’s first trip to London. And his, I will say it was quite fun driving around the campus with him, sitting in traffic. We went off campus, or off the property, the hotel to go to some meetings. And Tim got to experience London rush hour traffic.

Which I have to tell you, I’ve been going there for a very long time, and have spent a lot of time every year for many years there for work, and it’s gotten more hectic and chaotic. Great city, but my God, the traffic is tough sometimes. And so Tim, what were your impressions of London?

Timothy:Well it was great to get over to London. First of all, the weather was fantastic, I didn’t experience any rain, so no need for an umbrella. So that was great, number one. But, it’s always nice to get together with everyone in the industry, or the vast majority of the industry over there, representatives from so many different countries, from producers, to fuel procurement buyers, to traders and brokers, and investors, really wonderful to get everyone in the same place. And you’re really able to accomplish a lot, it’s so much easier to meet face to face, with so many people across the spectrum being there, and really jam your day full of meeting. So certainly useful and relevant for us.

Particularly coming off the back of 232, and what happened in July, we’re through the summer, we’re through Labor Day in the US, and I think a lot of people in the market who have been following this market for an extended period of time, are looking forward to getting into fall and back into the normal swing of business, if you will.

Mike Alkin:So just for your background, uranium is a very, would be characterized as a very niche market, it would be characterized as an incredibly opaque market. Information is … There’s information available but there’s so many stages of the field cycle, it takes a long time to learn. But, talk about your background in the world of cashews and the similarities with another opaque market. Tell listeners what your background is.

Timothy:Sure. So I started coming out of undergrad, started my career in Chicago as a futures and options broker, did that for a few years and got the opportunity to move to a large physical trading house, that was the most vertically integrated supplier of cashew kernels in the world. So my job was based in North America, and I was part of the sales and trading, the marketing arm of this company where we traded cashew kernels. And very ironically, or coincidentally perhaps, it was a fantastic market for me to learn how that works, how supply chains work, the opaqueness of having to really get on the phone and speak to people across the markets. Having to visit people around the world in the market, because you really had to get an understanding of what was real and what wasn’t.

What information was really … What was really going on in the market? Were people telling you real information? Were they trying to give you misinformation about the market? Because there is no exchange in some of these niche physical commodities, and there was not in cashews. There’s no clearing house, there’s no way to turn on CNBC or any of the main financial programs to find these prices, you really have to go out there and do the hard work yourself. Whereas in today’s world, with the electronic trade and the growth of information out there, I think investors, or the financial community can become reliant on, firing up their laptop, seeing the screen, seeing what the numbers are, and just becoming too reliant on that data. Versus actually getting out into the field, getting boots on the ground and speaking to individuals across the sector, to get a sense of what’s going on.

So for me, that was a fantastic opportunity to recognize that you really need to be going out and speaking to people, and you need to be going out and doing the work yourself and not relying on others, or simply looking at prices on a screen.

Mike Alkin:Yeah, so, I mean, it’s a very good point. When we think about uranium I mean it is complicated. And you have different forms of the fuel cycle, and you have, for those of you who aren’t familiar with the fuel cycle, it comes out of the ground, and a few different ways it comes out of the ground. It’s either mind underground, or in an open pit, hard rock mining. So that’s what you think of when you see guys down below with the lights on, on their work axe and, or an open pit, you see the big trucks going down. And, or it’s done institute leeching, or known in the US as institute recovery. Which is really just putting drill bits down in the ground, it’s flushing it out with a solution, bring it through a series of injection wells and recovery wells that separates the uranium from the rock, and it brings it back up, and then it all goes through a processing.

And then from there it goes on to a conversion facility, it converts it to a gas forum, UF6. From there it goes on to an enrichment plant where they separate the two different isotopes in the uranium and they enrich it up to four, four-ish percent for more nuclear power, over 90% for nuclear weaponry. And then it gets sent off to a fabricator where it’s put into fuel rods. And then from there it goes off to the nuclear power plant gate, where it gets ready to be inserted into reactors. And that could take a couple of years to do that. And there’s a lot of different steps, and it takes time. And so, these things in these uranium mines when they need to be built, uranium mines, arranged that not in my backyard nimby, right? There’s all this fear about nuclear around the world, despite the fact it’s the safest form of power generation.

And so, from the time of discovery or discovery looking for projects, looking for resource, to finding it, and permitting it, and licensing it, and financing it, which is not easy. Because, there’s a stigma attached to it. And people say, I … A lot of banks don’t want to finance uranium. So that can take you eight, 10, 12, 15, even longer 20 years to do that. So when you’re thinking about these things, what’s happening today, you need to think about the impact it’s going to have on the supply demand dynamics a decade into the future. Because it’s really today that those decisions today are made by that. And those decisions being capital expenditures and capital raising, and moving projects forward, because it’s tomorrow, 10 years from now in the world of uranium. So, a lot of that is dependent.

And because of that, I think sometimes that gets lost in the message, is people just look at today as though it’s real time today, as though supply could come online in a second, or demand could come online in a second. A reactor folks can take, the best reactors, the fastest reactors to come online are going to be five or six years normally. And you’ll see, the Chinese are building those in about five years. But the western builders, I mean, it could take 10, 12 years, eight, 10, 12 years, and significantly over budget, and they need to work on that, the West. The Russians and the Chinese can build them pretty quickly and typically on time, and on budget, or under budget. But these, the planning, I mean, again, is a decade and longer.

If you’re going to build one reactor, pick a number, I don’t know, you’re going to spend $8 billion to build a reactor. That’s going to take a decade to get that planning in place. So things that are happening in the market, when you hear people talk about 2030, that’s tomorrow, because those decisions need to be made today. So, it’s a very interesting dynamic that takes place in this world. So, with, we were talking about the nuclear WNA, that holds these conferences, and this one is a little different. Every couple of years they release their nuclear fuel report, as I mentioned earlier. And for the first time in eight years, they actually increased their demand projections to about, their reference case, which is basically a base case, right? They have a high case, a low case and a base case. It has nuclear power growing about 1.8, 1.9% per year.

Which if you listen to us talk, we thought 1.5%, but we are very conservative. We like to think in our projections of closures, and stats, and so on and so forth. So there was a upside there, but they really moved the lowercase up quite a bit from the dire projection. So that that showed a big step function increase. And, they talked about, for the first time, in a long time that the market is coming into balance. It’s important to understand though that, in their fuel report, they talk about what’s needed for that to happen and why it is a source of supply called unspecified supply. And, you have idle projects, and those are price dependent. And the WNA is by its own mandate, just through for historical purposes, and for some legal liabilities, don’t analyze the economics or projects. So you can have a market imbalance in theory, but then there’s the real world economics of the price required to bring that market get into balance.

And the report does a nice job of talking about that. But, it was a very different tone from, and I’ve been going to these for quite some time, and from what you’ve seen. So anyway, Tim, talk about what you know, I joke about that you being active on Twitter, and you’ve been able to give me some relief from … And you like to do a little bit of battle once in a while on there. But, talk about your impressions from the WNA, and some of the things that we look at from the perspective of where we could be wrong, and what we’re always trying to triangulate to see about. Where we could be wrong and what we’re figuring out on that front?

Timothy:Yeah, I would say that the tone of the conference was, particularly from a producer, an investor standpoint, cautiously optimistic. I think it’s very important, relevant that the industry, the entire industry, see some supply and demand numbers, and even though as you say, prices or costs are not available in the WNA due to some of the antitrust issues, it’s a much closer view, or reality to the years past, when the report has come out. And I think that’s very important. Because what it’s really doing is it’s identifying a lot of the positive things that have gone on in the industry, whether it be reactor extensions, countries altering their view on nuclear power and pushing back closures in some of the OECD countries in Europe, and the United States.

So to be able to bring all that information together into one report, and show that the dynamics in the industry are changing, particularly against two, four, six years ago, I think that was very important for people to see. I think it was important for utilities to see that changes are happening under the surface, we’re seeing changes in the fuel cycles. Whether it be in the conversion markets, in the separative work use, the SWU markets, with prices changing a bit. It’s important for everybody to see. So, I would say as succinctly as I can, cautious optimism was the phrase that would probably best represent what happened at the WNA last week.

Mike Alkin:And it’s interesting, because a fuel buyer doesn’t want to be, they’re not optimistic, that’s a good point though Tim. But a fuel buyer like, they don’t want to be optimistic about rising prices, right. To them their best friend is lower prices, so from the supplier side. But the whole thing about this industry that makes it so unique is the price reporting function of it. You need to think about the markets, and in any market that you’re looking at, is you have to understand what the market is. In the world of nuclear power, there’s the spot market, and then there’s the term market, or the long term contract market. And then you’ve had developed over the last several years, because of low interest rates. You’ve had the midterm market, if you will, which is really like less than, it’s less than five years or so.

And what the Genesis is with the interest rates really low, you’ve had brokers and traders go out and create a carry trade, essentially. Where low interest rates enable them to … And fall, and constantly falling prices would enable the traders to go out to the utilities and say, listen we know you typically, the vast majority, the overwhelming majority of what you buy is on long term contracts five, seven, 10 years. But as those contracts expire with the market and so much oversupply which it had been in ’12, ’13, ’14, ’15, ’16, ’17, why enter into long term contracts the price could keep dropping. And as a result you know what rates were low? We the trader, or a big investment bank, could use our balance sheet and take advantage of low interest rates, and our cost of money, which is their cost of money is fairly cheap as rates were down and say, let’s enter into a couple year contract.

And we’ll provide you the inventory. You don’t have to tie yourself up though into long term commitments at higher prices because who knows where the supply is going to end? And the utilities played it beautifully for years, and it made sense. Because if you think about this fuel cycle, and Tim you and I talk about this a lot. The uranium miners for years, played it wrong. And if you think about this setup for this cycle, 2011 in March Fukushima happens. Within a year or two, all the 54 reactors in Japan come off line. That creates a supply glut, that’s 13% of world’s supply came offline. And yet, so that’s a big chunk of demand that’s not there for uranium. But, there was something lurking out there that the market was looking at, and keeping their attention on which was called the Russian HEU, highly enriched uranium agreement, or affectionately known as megatons to megawatts.

And in 1993 when the US was concerned that the wall had just fallen, and they were worried that Russia was broke, and that some of those intermediate range missiles, nuclear warheads would wind up in the market because they needed money. They said, “You know what, you down blend them and we’ll take the uranium.” Down blend them from highly enriched uranium, which can’t be used in a nuclear reactor, to low enriched uranium and we’ll take that. Well, that was over 20 million pounds a year of secondary supply. Now, for context, take the biggest mines in the world, Cigar Lake, MacArthur River, 18, 19 million pounds a year. So you basically had the addition of a big mine in the world from ’93 to 2013. And that was a tremendous amount of supply coming out in the market.

But the market was thinking, well, you know what? 2011, 2012, 2013, yeah the Japanese it’s 30 nuclear power, 30% of the electric grid, it has to come back online. How can they not? And oh, by the way, look at this, 2013, you’ve got the end of this megaton to megawatts program. So what did you see? Right if you analyze the market, you go back and look at those bull cases in ’12 and ’13, and ’14 and ’15, ’16, you’re missing some real important things. Yes, you did have 20 something million pounds come off the market from that program, but replacing it was really a technology shift that occurred a few decades before in the enrichment part of the process of the field cycle. Where, the technology went from old gashes diffusion enrichment, to centrifuge technology. And it cost about one 10th of the cost of electricity to run one of those.

And so if you’re an enricher and you had all this excess capacity, because demand was down, you were able to extract more uranium, enriched uranium product than what the order called for from the nuclear power plant. And we won’t get into physics, it’s called under feeding. And I’ve talked about it before, you can look it up, I’m not going to get into a physics discussion here. But because of excess capacity in the enrichment phase, and because of the cost to run it, this time around was so low, you were able to put another 20 million. You were displacing the megatons to megawatts program basically, in round numbers. So, you have people thinking the Japanese went through all these safety checks, and even today, only nine of the 54 are online, and the max potential right now is 42, but we don’t think it will be that much coming back over the years, who knows.

We think that’s worked into the price of inventory, into the price uranium now. But, you had that going on. So you had this … So you had during this time period ’12, ’13, ’14, ’15 uranium mining companies spending more on exploration, producing more every year. So they’re exploring, spending on future project development. You had the world’s biggest mind come online Cigar Lake. You had the Kazakhs who are now the largest, the state of Kazakhstan is the largest provider of uranium. Half of that is through joint ventures, half of that is through their own production. They devalued the Tenge, their currency. Today it sits at 380 somewhat Tenge, and it was 180 back in ’15. And they cost in Tenge and sell in dollars, so that was an arbitrage for them. It saved their bacon.

But all that was going on, yet people are jumping up and down and saying, “Buy uranium stocks, the Japanese are going to come back online.” Tim and I, right how many bull cases Tim, did we examine that going back through those years where you’d say, you got to be kidding me?

Timothy:Numerous.

Mike Alkin:And when you look at that, you now are looking at a different market. What happens though is people get fatigued, right? So there’s different bull cases, there’s different time periods. So now you have to look at it, so now you’ve come at it from a bear. So Tim, come at this with a bear’s lens, come at the uranium market. Give us the bear case and give us the counterpoints.

Timothy:Sure. There’s a couple key points that some of the bears like to make. One of course is going to be inventory. That, some of the quota numbers out there, that there’s 1.4, 1.8 billion pounds of inventory out there, so why on earth could prices go up under this scenario? And of course, we need to provide some context to those numbers. One of the first key points to understand is that the bulk of those inventories are in the key details. So, that’s just a fancy way of saying that the natural uranium has been through the entire fuel cycle, that material has been enriched and delivered to fuel fabrication utilities, and the leftover little bits of the important atoms that you need to pull out of the natural uranium, the U235 part, is now less than a storage facility somewhere.

Once that happens, while it’s technically available to come back to the market potentially, there’s a very, very little chance to do so because of how expensive it would be to do. The technology to do so is a little prohibitive, cost prohibitive to some extent. So, you really need to take context as to where the inventories actually are. And when you’re able to break those down across actual utilities, across government stocks across traders and brokers, what you find is that inventories are not only within the historical levels, they’re actually touching the lower bound levels of those historical levels. Meaning that, utilities have relied some on inventories, as they should have since 2011 and Fukushima. But we’re approaching a time where utilities will need to change their playbook.

As you said Mike, the utilities have played this cycle fantastic the last eight years. But, you’ve got to turn a page at a certain point and recognize the market dynamics are changing, and that it makes sense to go cover your future needs where you need to do them. So, inventories are going to be one of the major key points that you’ll see from a bear. Anything to add to that Mike?

Mike Alkin:By the way, you should when you when you think about how it’s characterized from you know, WNA would say that, when it comes to the mobile quantity of commercial inventory is very important. They say, pipeline is strategic inventory, there’s pipeline and strategic, strategic means security supply, pipeline is throughout the fuel cycle right there. And there’s varying degrees to mobility in those. And the two forms of commercial inventory, are pipeline and strategic, they will say, constitute the vast majority of commercial inventory. And, when you look at it from a pound’s perspective, I think the number they, their, boy I don’t want to talk about their numbers.

But if you summarize what you learned from there was that I think the summary would be, if they’re concluded would be the mobile quantity of commercial inventory applicable, the future supply is only that volume deemed surplus or excess to the strategic and pipeline quantities of the total, and therefore represents only a small portion of total inventory. So I don’t know we’re not going to talk about their numbers. But when you do the numbers, and we do our own numbers, we’re comfortable to think that from a commercial inventory standpoint out there, you got a little over two years, a little bit more, but not much more. And it’s very common for these utilities to keep a couple of years of inventory around. So, that’s one of the big things you hear about, and we spend a lot of our time. And the question’s so, and one of the things Tim about inventory you think is, and it’s not like, you’re not seeing the monthly stocks report, whether it’s copper, zinc or lead, you don’t have that here.

You got to go find it. And you got to go look at producer balance sheets, you got to look at, seeing how much inventory they have. You’ve got to go look at each different region of the world and look at the utilities. And there are some agencies that do that, but not all of it. So it’s not wrapped in a bundle every month as to where it sits, when you’re looking at the LME stuff. So it’s art and science, but you have to understand strategic levels and pipeline levels. And, Tim we talk about all that you hear about all that, the inventory sloshing around out there. Let’s talk about pricing. Talk about spot pricing. And-

Timothy:Yeah, absolutely. I think it’s a very well-

Mike Alkin:… And as a trader of cashews.

Timothy:Yes. So it’s a very relevant point-

Mike Alkin:No, and how it relates.

Timothy:… To talk about prices and relative to inventory levels. And something that we’ve been spending a lot of time recently over the last many months is asking as many people as we can, if there is a view, a consensus view is that there’s a lot of excess inventory still out there. That uranium is extraordinarily plentiful in the world and not spoken for today. If that’s the case, why have we not seen new lows in 33 months? Because if I’m a trader, and my job is to be buying and selling in the market on a near daily basis, or shortly on a weekly basis, and we have a bearish view on the market, and we’re worried that there’s a lot of inventories out there, and there’s a lot of supply out there, I can assure you that my boss would be telling me every single morning when I came to the office, to be hitting every bid, and getting rid of any stocks that we have, whether it’s liquidating net long positions, whether it’s initiating short positions.

Because there’s no reason why we should be holding on to material if we think prices are going to be lower tomorrow. And it’s a question that really hasn’t been answered in a satisfactory way to us. So it’s something to think about, why can’t prices make new lows if indeed there was all this excess supply out there?

Mike Alkin:That’s a good point. And it’s a question we can’t get answered from traders, we can’t get answered. And you know, we talk a lot about price discovery. And, if you think so some of the common views are right, so a couple of things. On the production side, people will say, “Well might mean the Kazakhs could come out and ramp production tomorrow. They could add a seven million pounds for $100 million dollars. And, now context is everything, right? You have to think about, when you’re thinking about this right? So you see these comments that are out there, so let’s talk about that. So how much of the world really does get produced by that, by the Kazakhs? And yeah we take it a step further and we like to think about, okay, well, the, because conventional wisdom is, well, state owned entities don’t care, they’ll sell it at anything.

And actually in the WNA report, they say just the opposite. They say most state owned entities are cognizant of where pricing will be, and they don’t want to sell it at a loss. And that it is very important to them. So when you think about it, you think about well, all the state owned entities, well you got to think about that. You put it in different tiers. How many could produce below $20? Well, there’s about 87 million pounds of productive capacity below 88 million pounds. Below $20 cost, again, we’re going to round up the world uses a couple hundred million, about 10 or 11 of that is Olympic Damn, it’s a byproduct sold by BHP down in Australia, uranium is a byproduct of copper, so it’s really functional copper price that it’s dealing, but they don’t care what the price of uranium is, they’ll sell it anything in that tier is about but 10 or 11 million pounds. You got the Uzbeks capacity about seven, eight million pounds in that, but the rest are really Kazakhs and the Russians, uranium one.

Right. So that’s 88 million pounds, if everyone, so it doesn’t care but the average cost in there is probably, if you look at it, all in sustaining cost AISC, and you look at the Kazakh, and you look at the Russians, and you look at the others, they’re going to show, you got to remember how these, all in standard cost, that’s at the mine level, but you can’t run a mine if you can’t run a company. Right? So if your consensus all and sustaining cost in that tier is about 15 bucks a pound, when you start going through and doing the math, adding corporate GNA editing, interest expenses, and adding other costs associated to generate the free cash flow that you’re trying to generate, or generate cash flow you’re in 22, $23 range, about that.

But again, that’s 87, and by the way they produced in 2019, they’ll produce about low 60 millions. So if you think that they don’t care about economics of the 88 million pounds, you’re in the low 60s in terms of production at that rate. And they can produce, these aren’t limitations, that’s capacity, and they’re not, so it doesn’t matter. And then you start to get into the 20 to $30 cost. Now this is all in sustaining cost again, at the mine, not what it really costs to run, for these companies to stay in business. And then you start to get into another 30 million pounds. Of which, one of them, 18 million pounds a year, so you got like a couple million pounds is one call for a mile, make that 10 million pounds sitting there, with costs right now from state owned entities above where it is right now. Above where uranium’s selling when you add in the corporate costs.

So being produced at those that could produce under 30 bucks a pound, it’s about 90 million pounds. Again, it’s 200 million of demand round up, round down, depending on you know, but you’re in that ballpark. And the capacity there is, 119, 120. The other thing you hear, and then you get all the others, and there are some state owned in the others. As you go further down the cost there’s a few, there’s some Chinese, some Russians, with cost in the ’40s and ’50s and ’60s. Now if you took all insensitive price producers, little over 125, you want to push up to 130, you want to just throw in a few others, again, with much higher costs. And then everyone else is profit seeking.

And then so you here well, they live off of long term contract prices. So that’s the other thing you hear quite a bit about. And well, the reason they’re staying in business is because they have all these much higher price contracts. And again, these contract’s typically seven to 10 years, if you’re thinking about. It’s typically what your timeframe would be, and you say okay, well, yeah, geez, okay, let’s think about that. So, doesn’t matter, these guys are pumping out at much, much higher prices. Well, again, like everything, you have to take the narrative, and you have to kind of drill down through and see what the industry looks like. Right? What price is. When were those fancy contracts? Where they were really getting a lot.

What were the prices paid there? What were long term prices when they were really high? The average long term price in a year. 2012, average long term price, again, seven to 10 years, some five years, but about seven, eight years a good average. 2012 the average long term price was about 60 bucks. This is industry wide 2013, 54. Now a 2012 contract is about done right now. 2011 contract is pretty much done right now, at the seven eight year mark when that $66 uranium moved down to 54, 46, 46, 39, 31. And the volumes that were being entered into dried up completely. Not completely, that’s a mischaracterization. But, five one prices, were starting to ramp, buyers were higher, they were contracting in 2007, 225 million pounds, at average price of 95 bucks.

2013 they contracted 24 million pounds, and it’s gone up ’50s, ’70s, ’80s in that range and some of that’s Kazakh. Again, those contracts are Kazakh. But if they all produced at these levels, it’s not enough to fill the bucket, you want to add a few more million pounds with Kazakhs, it’s not enough to fill the bucket of demand that’s needed.

Timothy:And I think it was telling at the WNA as well, Mike, when we heard we as [inaudible 00:58:10], the leaders of Kazatomprom get on stage during the fuel report. And, for the listeners that don’t know, Kazatomprom produces some of the lowest cost towns in the world. And for [inaudible 00:58:24] to get on stage, and to say that the signals today are not there to bring on supply. And that there could be turbulent times in the coming years, I think is very telling. Because from my view, from our view, I think that Kazatomprom, now consensus won’t agree with us but, Kazatomprom is sending a very consistent message for the last few years. And we know that they had some rocky communication issues as they went public, as they were going public and continue to address this.

Is that this is a kind of the famous Ronald Reagan, quote, “Trust but verify.” I think the Kazakhs at this point have earned the benefit of the doubt to trust but to verify. And to keep a close eye, but they consistently are telling the market the same thing. And that is, prices even for them are not working today.

Mike Alkin:Yeah. We were, there’s … One of the things that they … And we were not at, there was a TD Securities conference on Tuesday, we weren’t there but we heard from multiple people there. That when asked can you cut more than that 20% production cut? Because they have sub soil use agreements there and it’s plus or minus 20%, they could increase at 20 or cut 20. And then after that, you got to jump through hoops. But asked directly, the CEO of Kazatomprom said, “Yeah, we can. If we need to, we can.” So these are, economics matter, again, of that those tiers, when you think about those first two, again that’s, you can’t look at all in sustaining costs as the minor show you. Because that’s not what it costs to run the company. If you’re Kazatomprom, you’ve got $200 million in dividend payments you got to make to the sovereign wealth fund in ’19, and ’20.

And when you do the math, you want higher prices. If you’re Chinese and you’re running Husab mine in Namibia, where your costs are astronomical, and you need to, because you got commitments, yeah, you’re going to do that. But Uranium One cares, the Russian owned foreign business of Uranium One, they care what they sell uranium at. Internally, their Armz A- R- M- Z business they care what it costs to mine uranium. But again, you got to look at the math. 90 million pounds, and those sub $30 cost, and again those aren’t the real cost, because you’re not adding in all the other costs, that’s what you got. And then all these other ones, you’ve got these contracts expiring that miners will have to keep production offline. They’re profit seeking entities, no one’s going to finance these things.

Forget about financing future projects, and that just squeezes probably even further. So we look at that, right? That’s part of what you have to look at. And if you’re doing your own analysis, do that. Take an all in sustaining costs that a company will tell you, whoever the company is and then ask yourself, does that include a corporate GNA per pound? Does that include interest expense per pound? Does that include the royalties per pound? Does that include dividends they have to pay? Because those a real cost, they don’t go away. And ask what they have to sell uranium for. To Tim’s point earlier as to why you don’t see it bursting out to new lows, if you got all these concerns about commercial inventory, that’s kind of where we’re at.

Because these are real costs, they’re not make believe costs. And when you’re looking at a, when you’re doing your analysis, and you’re looking at a feasibility study, a pre-feasibility study, you got to remember those are, I mean pie in the sky best scenario cases. We had a big fudge factor to those numbers. And the same thing here, the all sustaining cost isn’t a gap metric. Drill down further, ask yourself so when you’re doing your analysis look down on that, and it’s very important to think about that. We at that part of it … So it’s a cost, and that’s one of the things you hear, they can bring on production, they’re going to do it, right? Yep, they’re going to do it. Then go ask yourself and look at, go ask yourself for Kazatomprom, what the Westfield development expenses are.

And do they analyze whether those are extrapolated from a period of low investment or high investment? But again, let them all bring it all online. Doesn’t fill your gaps. On the demand side, yeah, sure, we’re showing up in London, we had no idea. We have our numbers, 1.5% growth, yep, it’s a growth business. We had no idea that they’re going to come out and say their reference cases 1.9%, for all, we knew they could have said it’s 0.5, make a number up, check. On the supply side, do your own math. When were the contract signed? Now one of the things you see is the price of conversion. Tim why don’t you talk about conversion and the pricing, and how there was so much conversion, all of a sudden what happened there.

Timothy:Right. So just as a quick reminder, conversion is when you take your UCLA, your natural uranium, and that you pay a converter to convert it to a gas, uranium hexafluoride, UF6. And the price that you pay is the conversion price. And it’s effectively a service that the utilities will pay to have this done. Going back approximately one and three quarters to two years ago, prices were wildly unsustainably low. We reached a low of about $4.50 cents, $4.50, $5, and those economics do not work for conversion facilities. So one of the major converters, the only converter in the United States, Converdin decided we can’t do this anymore, we’re not going to do this, so we’re going to shut down our entire capacity.

Fast forward to today, those prices are now $20 in spot market. So they’ve gone up multiple times. Now conversion runs on its own set of supply and demand, so separate, and this is a key point too, maybe I’ll touch on it now briefly. But every stop in the supply chain and nuclear fuel cycle runs on its own economics, conversion, as well. So when we see a market move into a massive supply deficit because capacity from Converdin came offline, and prices moved multiples, this has got to be a serious wake up call to the industry that the economics of this commodity and the entire fuel cycle are so out of whack, that something has to give. And for conversion, it’s clearly been given at this point, we’ve gone up multiple times.

Mike Alkin:And I’m going to interject for a second because this is important in how the opacity of the fuel cycle is. If you read the Expert Commentary 18 months ago, there was nothing to worry about. Pricing was fine, you’re fine, there’s excess capacity, yeah, they shut it down don’t worry about it. There was no one ringing an alarm bell. And then what happens? Should it be at 20? I don’t know, probably not. But should it be at four? Definitely not. But because of a complacency in a long bear market, you just kind of assume things are going to just kind of, yeah they’ll be there for a while. And then all of a sudden, it just kind of feeds off itself, and then fear kicks in, oh my God, I can’t get conversion. And then next thing you know, you’re up 5X. Tim, talk about the next phase separate of work units, which we hear a lot about, the under feeding aspect of this.

And, under feeding as we were saying, that essentially brought another mine into the world. Enrichers have excess capacity, SWU, separative work unit, they had excess capacity.

Timothy:Yeah, absolutely.

Mike Alkin:And because of the excess capacity, they were able to extract more enriched uranium product than what the orders called for. Won’t get into the physics of it, I’ve described it before about make believe it’s an orange juice machine, you squeeze a little bit more, and you get some out. But at the end of the day, it was a big, big source of secondary supply. And all these guys jumping up and down at 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 by uranium, never mentioned it. Not that we could find anyway.

Timothy:Correct.

Mike Alkin:But it was huge, it was huge. And, those prices of separative work unit, went from close to $200 per separative work unit, back to running the bull market in the mid 2000s, to a low of about 34 bucks, back about 18 months ago. And today it sits at 47-ish, but Tim talk about the buildup to separative work units and what you’re seeing with, what we see with capacity and the dynamics taking place there.

Timothy:Yeah, absolutely. So as you mentioned earlier in in the conversation, post Fukushima there was a lot of excess capacity generated in the separative work unit, the SWU markets from Japan, no longer needing that part of the fuel cycle to a large extent. Because of that excess capacity you touched on, you saw under feeding of the enrichment of tails, and the only reason that they could do that was because they had the capacity to do it. With the centrifuge technology, you can’t turn them on and off. Once you turn a centrifuge off, its off forever. So-

Mike Alkin:Once you turn it on, yeah.

Timothy:… And you have a centrifuge-

Mike Alkin:Yeah, yeah once you turn it off it’s off forever. And then once you turn it on it’s on forever, so, yeah.

Timothy:Yes, yes, so you don’t have the flexibility and capacity. So when all this excess capacity will generate, and by the way, let’s note that the cost to build enrichment technology, is extraordinarily high, very, very expensive to do. So you’re not going to just turn these things off if you’re an enricher, just help satisfy and balance the market. You’re going to go off and do what you need to do and that’s that. So we saw prices fall, as you mentioned from about the high 175, 200 down to 34. And over this multiyear process from 2011, 2012 to 2017, 2018 is, we saw optimal tails go lower. Now, without getting too complex, effectively what that means is, there’s a formula in the market, in the industry that generates what the optimal level of tails as they should be.

And that’s, how much do you draw down that U235 in the enriching process? Now, what a lot of people have missed over the last 12 to 18 months is that, as utilities were signing new contracts, limited contracts with lower optimal tails, that uses up more SWU capacity. So that-

Mike Alkin:And it’s nonlinear. It’s-

Timothy:And it’s nonlinear.

Mike Alkin:Yeah. As you drop your tails, you use a lot more capacity.

Timothy:Correct. But nobody really thought about this and figured this out. So as prices were falling from 40 to 35, to 34 everyone said well, this market is just going to do this forever. But, with the lower optimal tail contracts brought more SWU capacity, the enrichers needed to stick the material through the centrifuges more and more and more, to get to the lower optimal tails. To draw out the needed U235 atoms that they need to fulfill the contract. As they use more capacity, the market has rebalanced itself in SWU, and we’ve seen the market go from 34 to 45, 46, 47, in that range, this is a very unexpected development. Almost no one on earth thought SWU prices would go up 12 or 18 months ago. So again, you can’t just extrapolate linearly moving forward, just because prices have gone down. You really [crosstalk 01:10:47] dynamics.

Mike Alkin:I’m sorry.

Timothy:So again, it’s an unexpected development, we’ve seen in conversion, we’ve seen it in the SWU market. So that kind of leads us, just our thought process to say, well, if this can happen to conversion, where we see supply deficits, if this can happen in the SWU market, where we see the market becoming much more balanced due to the mathematics of enriching, surely, a supply deficit in U3o8, will have some sort of analog effect. Now while a lot of consensus out there doesn’t believe that, surely we feel a bit differently.

Mike Alkin:I just want to do one thing, I want to go back to the inventory talk, we were talking about inventory numbers before. Those are exclusive of China, and that’s one thing we should have brought up is China has their own inventory. They’re on their own massive build internally in the country. And most of it is just for strategic reasons, no one knows the exact years of inventory, but suffice to say it’s many years more than the average utility is going to hold. And while they’re not buying as much as they used to, they’re still buying a significant amount of uranium. So when we’re talking about inventory numbers, it’s exclusive of that, and the actual WNA numbers were reasonably below what we were expecting in our models as what the numbers were. But, I just wanted to kick that in.

So when we talk about, you know you talk about this, we see the conversion, you see the SWU again, they’re all different, their own economics and the economics of mining has to do with, and we talk about it a lot, and that’s what we’re always looking for is price discovery. So some of the things that we keep our eyes on is, where could we be wrong? I mean, is there too much spot market uranium floating around? And you hear on the conference calls, excess surplus disposal in the spot market. And this is kind of where, Tim explain the spot market in uranium to people and kind of how it works. And how in the grand scheme of things, the definition of spot for uranium, the time length. And does excess spot in uranium mean it doesn’t … And the correlation between actual supply and demand in the market and what’s going on?

Timothy:Yeah. So the definition of the spot market in uranium is, unlike anything, I’ve seen in commodity markets. And what I would call a “normal commodity market”, a spot market is here now, maybe a couple days in advance. Meaning that, if I’m a supplier, and I have an end user, and I sell to them on the spot market today, I’m going to go send the information for that consumer to go pick up that material today, and they’re going to pick it up today, tomorrow, maybe they’ll wait until Wednesday to pick it up. But that deal has been transacted, it goes on to the buyer, and it’s theirs. In uranium so spot definition through industry standards is up to 12 months. Which is very unique for a commodity.

So what effectively ends up happening is, it becomes a flawed arbitrage market. Where someone could sell on the market and literally produce into it, because they have the time to deliver it. Which is much different than any other market that would have to be fulfilled via inventories above ground because it needs to be delivered to the customer here and now. Similarly, the volumes transacted in context of supply and demand is very different from what we see on annualized supply and annualized demand. If buyers step out of the market, and buyers typically are the utilities, then there’s some traders in there as well. If they simply decide not to buy, say during the month of September, you could see lower prices.

Why? It’s the very basic plumbing of markets. [crosstalk 01:14:50]-

Mike Alkin:Or February or January, he’s not saying September, meaning that it’s any month.

Timothy:Right, I’m theoretically just saying that just to cite an example. If there are no buyers in the market, and there’s some sellers coming in because they have production, or they have some inventories that they just want to get rid of for any reason. Maybe they just want to get it off their books, maybe they think the markets are going lower, who knows. But the spot market is just a snapshot of liquidity today, that’s all it is. So if there are no buyers there today, and there are sellers there today, yeah, you could see prices tip lower and go a bit lower. Similarly-

Mike Alkin:And conversely, they could whip higher too just on the presence of a few buyers.

Timothy:Correct.

Mike Alkin:But that doesn’t, you’re not buying enough in the spot market to solve your long term security of supply needs as an electric utility.

Timothy:Right. So the best way I try to describe it to people is that, it’s just a snapshot of today, of the willing buyers and sellers. Now a utility may need to cover their needs for the next couple years in a pretty meaningful way. But, you’re not seeing that liquidity, you’re not seeing that buying interest in the spot market. So, the buying and selling interest you see in the spot market today, has very little to do with the structural supply and demand of this market in a much bigger, in a more macro view, if that makes sense.

Mike Alkin:Yeah, no, no, to me it does so. Well, what do I know? So, here we are, we’re talking, we’re kicking around inventories, because look folks, when we’re thinking about, I mean, we of course could be wrong. One thing about the markets is they’re always very humbling, and I laugh about that, what is it Malcolm Gladwell, 10,000 hours of, and you’re an expert, not in the markets you’re not. But we probably hit the 10,000 hour mark for sure. But it doesn’t mean we’re right. So we’re always constantly looking at, where are we wrong? Well, what can’t we figure out? Well, God forbid, there’s another nuclear meltdown, yep, that would curtail demand, people would get freaked out a little bit.

On analyzable, we think that, and very unlikely to happen but it can, a typical recession we talked about, well we don’t think it’s really going to impact it at all, typical recession. Is there a global financial calamity? Again, sure, I guess that could do it. Is the price of SWU so, so low, that they’re going to keep under feeding, and they have all this excess capacity? And that’s going to keep pressuring the market, that’s something we need to really focus on, we could be wrong there. And again, all the sources that we speak to and think about and know how to analyze, we don’t believe so, but it’s always something that you think about. We feel quite confident that it’s just the opposite. Obviously the political stuff that comes into play and you think about the last couple of years of, on the demand side, you’ve seen kind of a little bit of a change there.

You’ve seen the French who wanted to reduce nuclear dependency from 75% to 50% by 2025. Now, say it’s a 2035 thing, not a 2025. You have seen the US, the states have come in and many of the states have come in and supported the nuclear power industry. So some of those that were coming out. The Indians have come out and said they’re going to be adding more reactors, you’ve seen more throughout the emerging markets coming on, so you’ve seen a positive development. But hey, we’re always constantly, if you are investing in the space, you constantly have to be thinking about something like that. Are the Chinese going to? They’re a significant portion of the new build program, they want to go to 130 to 150 gigawatts by 2030, and they’re close to 50 gigs now, roughly.

That’s a lot of reactors, they have several under construction, but they’ve got to continue to do it, right? So that’s something we’re always keeping our eyes on. So there’s always areas you could be wrong. But price discovery and Tim talked about 232 earlier, a lot of those contracts, and this goes back to what I was saying about the production study. The complacency that kicks in, and the recency bias that kicks in, and the narrative is such, and where we focus a lot of our time and again, we think we’re right, we could be wrong. We strongly think we’re right, because we express our view that way. But, is that, there’s all this low cost production. And they could come on in a whim, well the numbers would show you that it doesn’t go anywhere near solving the gap.

That all this production would come online. And again we’re saying, bring it all online at below pricing, at below market prices. And it doesn’t get you anywhere near what you need. Then you could take it another layer and say, well, what do the numbers tell us? The numbers tell us that based upon the actual production versus the capacity, it actually does mean that there are economics involved even for those state owned producers, and they do care. And you see that. But their behavior has indicated that. So, you have to think about that on supply, and there’s all this thought that it’s just going to be out there. And then there’s, well, they’re living off these really high price contracts and that’s why they’re staying in production.

Yeah, well, the last time that it was below the marginal cost of production for uranium miners, was seven, eight plus years ago, and those contracts are pretty much running off. And supply will come offline and stay offline. And you have a number of, a handful of big mines that are producing, that come to their closer life in the next few years, a few of those. And then you have a real big mine that comes offline in 2027, that produces 18 million pounds a year. And that’s tomorrow, in the uranium world. And you need all these projects that are under development to come in to come on, you need some of those to come online to fill that gap. And those projects aren’t going anywhere until the price gets … So now you have this process of price discovery.

You’ve got this, this spot market, that is what it is, as Tim just talked about, and then you have this, the 232, section 232 created kind of a bias pause. And now you’re getting into a period where okay, bigger pounds are going to start to be contracted for. You’ve got the price reporters in the industry who have, the narrative is still cautious, but aware of some of the changes taking place. Again, people look to price reporters as the guide. I don’t think price reports were calling a 5X move in conversion pricing, and these things happen. Recency biases kicking in all over the place. And so, as you think about that, and you think about the process, and that’s things we see a lot too though when Tim and I are [inaudible 01:22:17] by people, we see a lot on Twitter.

People think, well how can prices move today? 232 clears, you’ve got around a price discovery, fuel buyers, by the way, are extremely bright people. A lot of their time is not spent buying fuel. And a lot of their time is not spent doing deep dive analysis of supply and demand. They use what they, they pay good money for price reporting for that, and data reporting. And we would disagree with the price reporter significantly. But … So where they really find out is when they go into the market, and they start to transact four pounds and these negotiations take quite some time and they go back and forth, it doesn’t happen overnight. And that’s how it market heels, right? And you start to sit at a table and you start to talk about it. And so, those are things that as investors you need to be looking at. Not reading headlines, not thinking about there was a headline that came out when we were in London, talking about uranium mining stalling because of demand waning or something like that.

It couldn’t be further from the truth, demand upside, there’s first time in eight years WNA took the numbers up and they said it’s the best market since the ’90s. So you can’t read headlines. But Tim, what other parts think people … Where we’re always trying to focus where we could be wrong? And when you, you know you get hammered a lot, not hammered but you’re always in a debate on Twitter. In terms of, the things that make you go, ah. Where it really … Where you’ll call me up and say, “Are you kidding me?” What are the things that make you go on a rant?

Timothy:I think it’s, for me, it’s a lot of the recency bias things. Mike you’re well aware that over the course of your career in deeply cyclical markets, at the highs or when things are going very well, things will go well forever, and when things are bad, they’re going to be bad forever. And we’re at a point in the cycle, and it’s normal at this point in the cycle, to see people deeply entrenched with recency bias. And, so what happens is they will start grabbing anything they possibly can, any rope that they can grab to point to say, “Aha, this is why the story is not going to change.” That is a big pet peeve for me. For example, just a couple of weeks ago, we saw the report come out that the Japanese were beginning to dump inventories into the market.

What really happened was, one utility, which was acknowledged by Cameco on their Q1 call many months ago, selling some small amounts of pounds into the markets just show their buyers could do something. The Japanese utilities have been sitting around for many years, most of which they literally done nothing for years and years. And they said, “You know what, we’re going to do a little something.” And that was the thing now that’s going to change the fundamental outlook on this market. And that’s a big thing to understand. That just because a news article comes out, you got to dig deeper, you’ve got to understand the context, you have to understand, is this going to change the direction of this market? Or is this just one little tidbit of information that’s being thrown out there?

But people latch onto it, and they grab onto it, and won’t let it go-

Mike Alkin:Without context [crosstalk 01:25:48]. I mean you’ve got to kind of understand how much mobile inventory is there, and what the context is. And are there other reasons they wouldn’t do that for corporate purposes? I mean, you got to be in there talking to people to understand these things. So when you’re reading headlines it’s understandable, but those are areas you got to drill down and understand.

Timothy:Yep. Maybe one other subjects we can touch on is that people use a blanket statement. First of all, no blanket statement should be used in this sector, because it’s far too nuanced. One is, that all utilities are the same. You always see it, if you’re on any of the Twitter or in certain news articles, it’s always utilities, utilities. Well, utilities are very, very different. There’s 60 some out there in the world of these individualization organizations-

Mike Alkin:In nuclear power.

Timothy:… In nuclear power. And I can tell you that utility buyers, we’ve talked with them, we’ve met with them, they’re very smart people, as you mentioned, they really are far more academically credentialed than I am. But we also believe in the 80/20 rule. We believe that 20% of the industry, pretty much 20% of any industry does 80% of the work. And I think that this sector is no different from that. That you will have your leaders in the industry poking around out there, trying to understand what’s going on, doing their own analysis. And then you have the 80% really just kind of following consensus, just following what prices are doing, not really getting deeper in any way. So it is frustrating to hear, oh well, utilities are going to do this.

Well, utilities are all different. They all have very different levels of knowledge, they all have different levels of what they’re trying to do, and how to analyze the market. So it doesn’t make sense to us to link them all together in a singular boat, if you will.

Mike Alkin:Yeah, no, absolutely. Well, so I took the, because I’m older and wiser, I took the Friday 8:00 PM flight home, and Tim stayed for the dinner for Friday night. And somewhere over the Atlantic, I was on Wi-Fi and Tim was texting me. And I didn’t think of it because when you’re flying, I was doing some work, and then it hit me, good God what time is it there? And it was 4:00 AM London time. And I said, well, you’re up. And he said, “Well, you know, gosh, these guys they could drink some beer.” And so at the gala wrap up dinner Tim was quite the champion, he got back at 4:00 AM and rather than go to bed, he went straight to the airport for a 10:00 flight. So I was impressed. I haven’t been able to do that in 20 years. So, how do you feel over the weekend?

Timothy:You know, I felt pretty good to be honest with you. But. I wanted to make sure that I did not fall asleep and miss my flight because I certainly did not need to have to make a phone call or text messages to explain that I was not coming home and being home on Saturday, early afternoon to mow the lawn and take care of some of the other things I usually take care of. So, I figured you know what, I’m going to just stay right up and let’s just head right back to Paddington and Heathrow express. Because then if I fall asleep, I’ll be in the terminal at least. So that was a good choice, I think.

Mike Alkin:Or you could have been like me and left for the airport at 5:30 for an 8:00 flight, a little bit late. But you and I had a very important meeting with a very worthwhile contact that we had beforehand. And we had a couple of beers before we left and I was going right from this meeting to the airport. And of course I had two pints of beer, which is my max that I ever have, but I forgot to go to the bathroom. From the time I had those two pints to the time I jumped in a cab to get the Heathrow. And it was Friday rush hour traffic, and about halfway there I was thinking, I’m not going to make it, I am just not going to make it. Not only that I thought I’d miss my flight, but here I am thinking I was going to pee my pants because I couldn’t.

And I said to the guy, can we pull off anywhere? He said, “But mate, you’re not going to make your flight if you do.” So it was, I made it by the skin of my teeth, I made my flight by the skin of my teeth, I made it to the John by the skin of my teeth, so it all worked out well. And that was a good way to wrap up what was otherwise a very good week in London. No rain, positive outlook from the WNA on demand. And by the way, this WNA is not where most of the US field buyers aren’t there. The big one for them is the NEI, the Nuclear Energy Institute conference that takes place at the end of October. Last year it was Boston, we spoke there, this time it’s in Nashville, that’s where you get the big fuel buyers from around the world getting there and sitting down there.

And I think Saghand corp will be presenting there talking about our view on certain things. But it was good kickoff to the fall season, and a period where you start to, all this complacency of years past I think is certainly being called into question. So we left there in pretty good spirits, very good spirits. So, Tim, thanks for taking the time, now go back to work.

Timothy:Well, I really appreciate it Mike. We’ll keep plugging along here.

Mike Alkin:All right, man, thanks. Talk to you later. All right, well, for those of you interested in uranium, I’m sure many are not. I thought that I’d bring Tim on, I was asked to bring him on. I was going to have my buddies from Segra on, they also run a uranium fund, but they couldn’t get the timing right today so, I wasn’t able to get them. Out of the office for a week, got to get back and tend to other things. They don’t have a podcast to do every Monday morning so. But I will, hopefully it was helpful. Again, I’ll give you a little snippet of what we do, not going to share with you too much of our financial analysis, that’s proprietary, but hopefully just point in the right direction on some things.

And again, this is a very, very strong conviction idea for us as the asymmetry of the risk reward is the best I’ve ever seen in my career. But, it doesn’t mean it’s right for you, it doesn’t mean that I’m right, it doesn’t mean, I think I am but, do your own work. And, do your own analysis, and come up with it. But hopefully we just kind of laid out some of the finer touch points and we could spend here hours as I’m sure we missed a lot of stuff. But, in the hour that we’re doing it, they tell me that if I do it really long, these really long, that people fall asleep. So I try and keep it relatively short. But anyway, I hope you enjoyed it. I hope enjoy the NFL season, and for those of you hockey fans, I know I have a lot of Canadians listening, that I’ll start to talk about what I think of the Highlanders coming up and you can get after me for that. But anyway, hope you have a good week and we’ll be back next week. Thanks.

Announcer:The information presented on Talking Stocks Over a Beer is the opinion of its hosts and guests. You should not base your investment decisions solely on this broadcast. Remember, it’s your money and your responsibility.